The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight (partially found footage of boxing match; 1897)

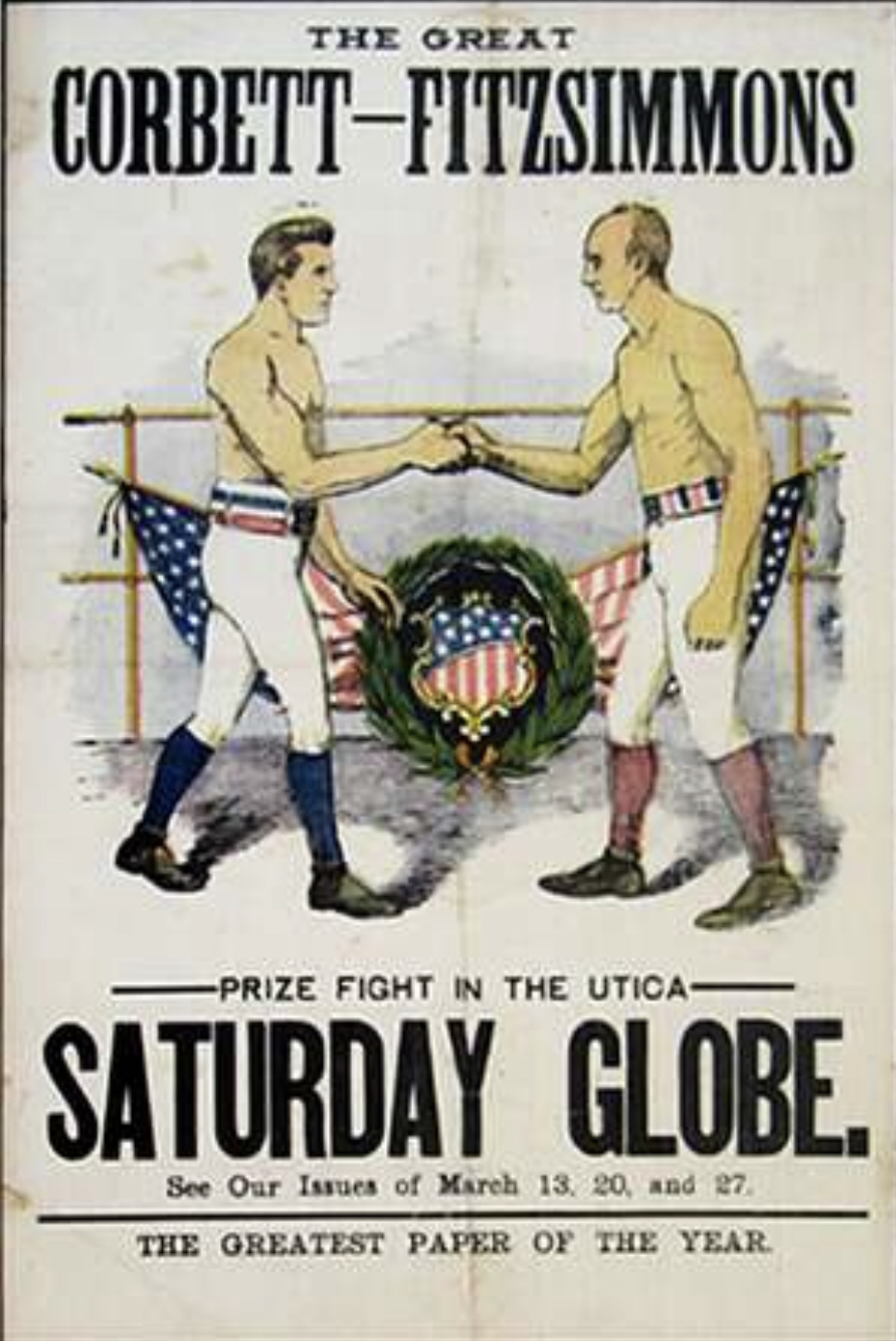

The bout promoted by the Utica Saturday Globe.

Status: The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight - Partially Found

Reproduction of the Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight - Lost

The Fight/The Finish - Partially Found

Representing the Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight - Found

The Big Corbett Fight/Prize Fight - Lost

On 17th March 1897, James J. Corbett defended his World Heavyweight Championship against Bob Fitzsimmons. It occurred at The Race Track Arena in Carson City, Nevada, where Fitzsimmons ultimately recovered from a sixth-round knockdown to end Corbett's controversial reign via a fourteenth-round KO. While already a historic bout in the boxing world, its legacy is especially felt in the film industry. This is because Enoch J. Rector's recording, titled The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight, became the first ever feature-length film. The production has also been cited as the first "true" widescreen work and the first heavyweight championship bout to be captured on film. It is additionally known that Siegmund Lubin filmed and released a supposed "reproduction" of the fight, which generated extensive controversy concerning piracy and false advertising. But most obscure of all, several flipbooks based on the bout were released by various companies.

Background

As 17th March 1897 approached, American boxer James J. Corbett was six months away from a five-year reign with the World Heavyweight Championship.[1][2][3] He captured the belt on 7th September 1892 after he beat defending champion John L. Sullivan via a 21st-round KO at the Olympic Club in New Orleans.[4][2][1] Amazingly, Gentleman Jim had only defended the title once since then, with a third-round KO victory against Charley Mitchell on 25th January 1894 at the Duvall Athletic Club in Jacksonville, Florida.[2][3][1] There were a few reasons for this: firstly, prize fighting of any kind was illegal in the majority of states.[4] But even when bouts could be lawfully arranged, the lack of boxing commissions made sanctioning official contests difficult.[5][4] Hence, Corbett primarily competed in exhibition bouts and also began a lucrative acting career.[6][3][4] Aside from minstrel shows and the occasional low budget movie,[3] his early film career also included a fight with Peter Courtney on 7th September 1894.[6] It became the second boxing bout to be recorded, released under the title of Corbett and Courtney Before the Kinetograph.[7][6]

But the biggest reason for the lack of title defences was that Corbett announced his "retirement" in 1895.[8][9][5][3] He decided to "award" the Irishman Peter Maher the championship following the latter's win over Steve O'Donnell on 11th November 1895,[10][11] in a move that did not gain overall consensus.[5][3][8] A few reasons for Corbett's choice included his own Irish ancestry.[5] Additionally, he had actually planned to award the belt to former sparring partner O'Donnell without a bout being required, but instead chose the winner of the Maher fight following public backlash.[3][10] Maher subsequently defended his World Heavyweight Championship claim against Bob Fitzsimmons.[12][13][5][10] At the time, Fitzsimmons had recently relinquished the World Middleweight Championship, having enjoyed an undisputed reign since his 14th January 1891 victory against "Nonpareil" Jack Dempsey.[14][15][12] Fitzsimmons had previously defeated Maher in a 12-round contest on 2nd March 1892.[14][5][12] Naturally, he contested Maher's dubious title claim, which he won on 21st February 1896 by KO after a single round.[5][8][10][12]

Fitzsimmons refused to recognise his first "reign", merely declaring it as a "championship present" by Corbett.[5] Still, Ruby Robert[15] would compete in a second "World Heavyweight Championship" clash, this time against Tom Sharkey on 2nd December 1896 at the Mechanics' Pavilion in San Francisco.[16][8][12] Officiated by none other than famed Old West lawmaker Wyatt Earp, Fitzsimmons controversially lost the bout by disqualification after he landed an unintentional below-the-belt shot to Sharkey.[16][8][12] However, whereas Sharkey also began to promote himself as the World Heavyweight Champion, the reality was that his, Maher and Fitzsimmons' reigns do not officially count, as Corbett had already reneged on his retirement by June 1896 and thus kept his status as the "true" champion.[3][5][6][16] Consensus also indicated Fitzsimmons had a more serious claim as number one contender than Sharkey, as the former had dominated their bout prior to Earp's decision.[16]

Thwarted 1894 and 1895 Attempts and Eventual Fight Build-Up

Interestingly, records from newspapers like The New York Times show a Corbett-Fitzsimmons fight could have transpired three years earlier.[17] The first indication of a future encounter came following Fitzsimmons' victory over Jim Hall on 8th March 1893.[18][12] In a post-match interview, Fitzsimmons was surprisingly humble, admitting he and Hall were in a class below the likes of fighters like Corbett and Paddy Slavin, but still reckoned he had a chance against them thanks to his right fist.[18] The first serious fight proposal started emerging in August 1894, amid negotiations between Corbett and black boxer Peter Jackson.[19][20] Indeed, if Corbett refused to face Jackson, the pressure would be on him to either defend the belt against Fitzsimmons or consider retirement.[19] Ultimately, Jackson's offer was ignored by Corbett because of the infamous "color bar" enforcement.[21][20] Initially, the champion also rubbished Fitzsimmons' challenge, having deemed him not at his level especially as Ruby Robert had primarily competed against middleweights.[21] After Fitzsimmons made a lucrative $25,000 offer for a bout at New Orleans' Olympic Club, Corbett responded that he might take the challenge more seriously if Fitzsimmons beat O'Donnell.[22] Fitzsimmons did have one notable backer: former champion Sullivan, who also accused Corbett of refusing to fight anyone.[22]

No records show a Fitzsimmons-O'Donnell match occurred during this period.[12] But by October 1894, thanks to efforts by the Florida Athletic Club, the men agreed to fight sometime near the future, helped by a proposed $50,000 film deal.[23][24] However, plans were scuppered under tragic circumstances.[23] On 16th November 1894, Fitzsimmons competed in a sparring exhibition with Con Riordan at the Jacob’s Opera House in New York.[14] The match ended with the accidental death of Riordan, which led to manslaughter charges being pressed against his opponent.[14][23] Though Fitzsimmons was acquitted of all charges, the reputational damage he suffered meant his proposed Corbett match would need to be postponed.[23][14] Fitzsimmons' next professional bout would not transpire until he defeated the debuting Al Allich on 16th April 1895.[12]

Almost a year following the incident, fight plans finally re-emerged by September 1895, with "Yank" Sullivan being considered to officiate the contest.[25] The bout's promoter was Dan Stuart, a Dallas businessman who headed the Florida Athletic Club.[26][27][28] Plans to host the fight in Florida were shot down, so Stuart attempted to secure an arena in Dallas.[26] But while the Dallas City Council approved the bout, the news did not please Governor of Texas Charles A. Culberson, who immediately sought to outlaw it.[29][25][27] On 27th September 1895, a special session of the Texas Legislature was called, which resulted in legislation being passed on 2nd October that made prize fighting illegal in the state.[30][26][29][9] Stuart's second backup plan was Hot Springs, Arkansas;[26][9] it appeared the move had local support, with The Hot Springs Railroad Company having begun a sidetracks project on 10th October to allow the city to cope with the sheer volume of visitors.[31] However, just like his Texas counterpart, Governor of Arkansas James P. Clarke was deadset against the fight occurring in his state.[32] While no legislative officially outlawed it, Clarke was confident Hot Springs authorities would prevent the fight from commencing.[33]

Clarke was ultimately proven right; in fact, arrest warrants were imposed on both boxers to prevent the match from occurring on 31st October.[34][26] While Corbett was shielded in a Hot Springs household that supported the bout, Fitzsimmons was arrested after he crossed state lines.[34][26] Though he was promptly released, it seemed inevitable the bout would not transpire anywhere in Arkansas.[35] Outside of a chance face-to-face encounter at a Little Rock dining room,[35] it seemed a fight between the pair would not emerge in any American state.[36] Though there was the occasional hope that a Mexican city might host it since prize fighting legislation was more relaxed across the border,[37][38] the hyped-up contest ultimately never emerged in 1895.[27][36][29] Shortly after negotiations broke down, Corbett announced his "retirement" so he could prioritise an acting career.[9][27][29] This, combined with the ever-increasing outlawing of prize fighting, caused a sequence of events where the World Heavyweight Championship scene degenerated into a disputed, "hide-and-seek" nature.[29][10] Despite the new Texas legislation, some El Paso businessmen were able to get Fitzsimmons vs Maher II to occur in a ring situated on a Rio Grande Canyon sandbar, just outside the Texas no-go zone.[29][26][5][12] This debacle and Fitzsimmons' subsequent vaudeville activities were apparently enough for Corbett to reverse his retirement decision.[27][5] This frustrated Fitzsimmons yet further, as he had embarked on a "victory" tour in England months prior.[13]

Corbett's return was somewhat of a dud, a four-round non-title draw to Sharkey on 24th June 1896.[27][1] Three months later, on 12 September 1896, Corbett and Fitzsimmons agreed once more to a match.[39] On 17th December 1896, the pair signed articles for a match via the Marquis of Queensberry rules,[40] with $15,000 plus bets on the line.[17] Though it was hoped the bout could take place in January 1897,[39] protracted negotiations meant it would instead officially take place on 17th March.[41] A few clauses were established in the articles: thanks to his manager Martin Julian's negotiations, Fitzsimmons and his opponent would be guaranteed an equal share of the revenue from a possible film.[42][41] The agreement meant the boxers depended entirely on Stuart's promoting abilities.[41] Additionally, thanks to the calamities of 1895,[26][27] Stuart was instructed to keep the match's location a secret until a month before it was held.[41] Julian believed the fight would likely occur in Texas or Mexico.[41] In actuality, Stuart focused on Corbett's home town of San Francisco,[43][2] whose Mechanics' Pavilion had recently hosted the Corbett-Sharkey and Fitzsimmons-Sharkey matches.[1][12] However, these plans were also scuppered.[43] Undeterred, Stuart capitalised on another opportunity that opened up: Nevada.[44][45][43]

Nevada was one of many states that banned prize fights.[44][45] However, the state had suffered a major economic downturn which began in the late 1870s, primarily because of the decline of the mining and ranching industries.[44][45][43] The population had subsequently fallen by several thousand,[43] prompting desperate bids to reverse the rot including via the legalisation of gambling.[45] This, surprisingly enough, failed to revive the state's fortunes.[45] However, with Stuart also desperate to promote the long-delayed match, a push was made to legalise boxing in the state.[43][45][44] Among Stuart's allies was legislator Al Livingston, who led the lobbying efforts towards Governor Reinhol Sadler.[45] Having accepted the economic benefits the fight would bring, Sadler signed the bill that officially legalised Nevada prize fighting on 29th January 1897.[43][45] This bill attempted to ensure professionalism, containing ten key regulations.[43] Among these dictated that any keen promoter would be required to pay a $1,000 licence fee.[43][45] Secondly, at least two licenced state physicians would assess the participants' conditioning before the bout took place.[43][45] Another critical point mandated that sanctioned prize fights would be exclusively glove contests.[43][44] As American boxing began the adoption of Marquess of Queensberry Rules, which mandated gloves and three-minute rounds,[40] this was of no concern.[44][45]

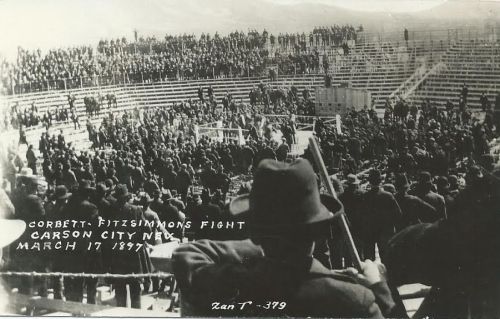

Once Nevada's legislation became public knowledge, it immediately triggered a backlash from other states.[45][44] The bout would soon be labelled "Nevada's disgrace", not helped by referee George Siler's admission the fight occurred because Stuart took advantage of Nevada's floundering economy.[45][44] When it was announced the fight would take place in Carson City, the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad refused to lower prices to accommodate an influx of boxing fans, with General Passenger Agent Francis having bluntly stated "We do not want any of this prize-fight business."[46] In the end, the backlash mattered little for Nevada, who started reaping the publicity benefits.[45] Meanwhile, Stuart oversaw the creation of a new Carson City ground, the 17,000-seater Race Track Arena.[44][1][12] The first boxing-centric open-air arena,[47] its capacity greatly exceeded Carson's population of fewer than 3,000.[44] Stuart therefore needed extensive publicity, which he got as national newspapers travelled to Carson to cover the build-up.[45] In the meantime, Corbett and Fitzsimmons chose Shaw's Springs and Cook's Ranch respectively to commence their training routines.[44] Special trains were also allocated to ferry in the fans.[48] San Francisco was naturally expected to bring in numerous Corbett supporters, while the state of Virginia had a large mining population which also greatly backed boxing.[48][44]

Stuart had also brokered a filming deal with the fledgling Veriscope, who engaged in the ambitious plan to record the entire encounter.[23][49][50][27] Whoever won the bout would not only become champion but would also earn a $15,000 purse, their opponent's $10,000 bet and 15% of the film's revenue.[17][50][47] With the fight officially agreed to by the boxers, sanctioned in a state that legalised prize fighting, and extensively promoted, the long-awaited contest, dubbed the "Fight of the Century" by some sources, was finally ready to commence.[17][48][47]

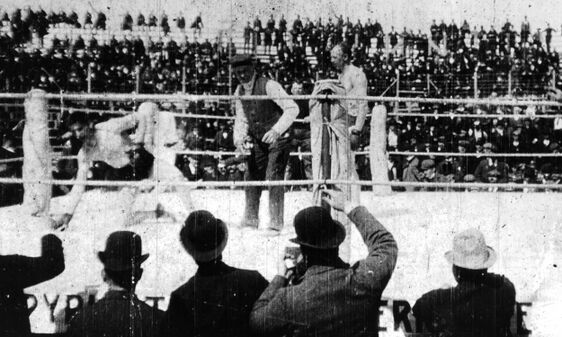

The Fight

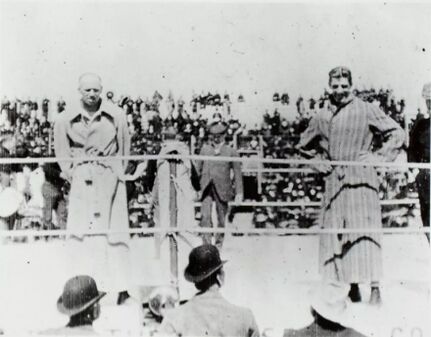

On the day of 17th March 1897, as St. Patrick's Day was also being celebrated,[47][44][23] trains from across the country pulled up at Carson City.[48] As expected, San Francisco residents turned out en masse to support their local hero.[51][48] What was less expected was the lack of fans from other places, especially in Virginia.[48][51] Ultimately, despite the bout's hype, the special trains ferried surprisingly few individuals.[51] In total, only a maximum of 7,000 (some sources claim between 4,000-6,000) attended the Race Track Arena,[51][44] with around 3,000-4,000 having travelled to the vicinity from other states.[48] However, those who did attend certainly made their presence felt, as they nearly overwhelmed gatekeepers upon making their way through the stadium's gates.[48][44] One interesting aspect is that the ringside and cheap seats sold nicely, but the middle rows were almost completely empty.[51] Demand for cheap seats prompted the decision to double their prices.[48] Those who attended early got to witness two preliminary bouts, including the middleweight clash between Billy Smith and George Green and the 54-second featherweight contest that pitted Dal Hawkins against Martin Flaherty.[52][53][51] Among notable people who attended included Sullivan and Sharkey, who both eyed a match with the victor; and Earp, who covered the bout for The New York World.[54][48][16][47] Earp and others brought guns into the vicinity, which forced Sheriff Bat Masterson to confiscate 400 of them before the bout commenced.[55]

Something also noteworthy regarding the attendance was the presence of women.[51] Even before prize fighting began being outlawed across the United States, women were typically excluded from what was viewed as a male-only sport.[56][54] On 24th February 1897, Stuart announced he would grant women access to the arena, having noted some "prominent" men were likely to bring their spouses along with them.[57] Anticipating the potential backlash of this decision, Stuart stated women were "the best judges of what they should and should not see".[57] Since this was the 1800s, there were some strings attached; women had to be accompanied by a man and sit in the so-called "Birds' Nest" area of the stadium.[51] Some women were among the first to eagerly enter the Race Track.[48] However, the stigma of prize fighting turned most away; according to the Nevada Women's History Project most female attendees were allegedly sex workers.[58] But there was a notable exception: Nellie Mighels Davis, who became the first woman to cover a boxing event, having also placed a $50 bet against a Mr. Woodburn.[58] Also in attendance was Fitzsimmons' wife Rose, who sat at ringside on her husband's corner.[48][51] She had originally backed out of seeing the bout but eventually changed her mind.[48] Rose would play a key role in the match's outcome.[59]

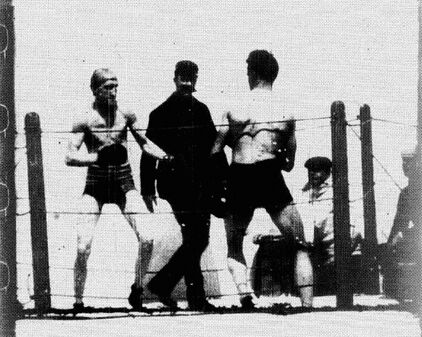

Both boxers trained hard at their respective Carson training camps, primarily so they could learn to cope with the city's high altitude.[47][44] Heading into the fight, Corbett was the 10/6 bookies' favourite.[48][14][45] On paper, it would have been perfectly understandable why Corbett initially rejected Fitzsimmons' early challenges.[21] After all, Corbett boasted a significant height and weight advantage, 6 ft 1 in and typically 178 pounds compared to Fitzsimmons' 5 ft 11 and a 1⁄2 in, 167-pound frame.[60][1][12][14] Though sources conflict regarding the boxers' weight pre-fight, most agree Corbett maintained the size gap between him and the challenger.[60][48][47] Corbett also boasted technical prowess, his gameplan of dodging and counter-attacks to achieve victory being something future champion boxers like Muhammad Ali would later harness.[4][2] In comparison, Fitzsimmons weighed no more than the average modern super middleweight, not helped by his welterweight legs.[14][15] But ultimately, his appearance meant little; his sheer resilience, punching power and knockout ability were what truly enabled him to outclass his bigger foes such as Maher.[15][14]

The boxers played mind games before their bout; particularly, an unexpected meeting between the pair almost led to an altercation over Corbett apparently not shaking hands with the challenger.[47] They were not the only ones feeling the intensity; hosting the fight cost America $2.7 million (almost $100 million in today's money)[61][47] Bets were also extraordinary;[47][48] The New York Times reported that over $100,000 was transferred over in the New York City region alone.[17] Minutes before noon, both boxers emerged in their elaborate dressing gowns.[48][47] While the pair received applause from the audience, it was Corbett who initially gained the most crowd support thanks to his San Francisco entourage.[48][51] Fitzsimmons, likely still reeling from that earlier incident, refused to shake a grinning Corbett's hand before the first round.[47][48] After Siler commenced his final inspections and instructions to each boxer, timekeeper William Muldoon rang the bell at around 12:05 p.m. to finally let Corbett and Fitzsimmons do battle.[17]

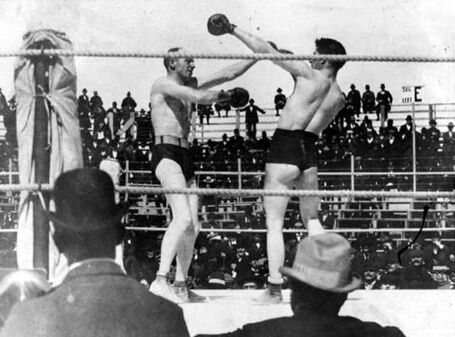

Round 1 was initially a cautious, long-ranged encounter. After circumnavigating Corbett's initial dance affair, Fitzsimmons missed his inaugural left swing as Corbett was trapped in a corner, though the champion's counter-attack also proved inaccurate. Fitzsimmons landed the first notable attack, a low-powered clinch uppercut. Corbett and Fitzsimmons then exchanged left shots, with the former's proving more effective. Corbett also landed a powerful uppercut, though Fitzsimmons was able to retaliate with his own uppercut to the jaw. Despite the challenger's offence, Corbett merely laughed it off. A non-impactful clinch ended the first round.[17][48][47] Round 2 firstly witnessed clinches and Fitzsimmons failing to properly land his attacks. The challenger was being mightily aggressive, though Corbett's fancy footwork enabled him to dodge his foe's corner attacks and respond with a left swing and a right body blow. Though Fitzsimmons landed a left uppercut, he could do little against a barrage of left shots to the ribs and stomach, Corbett's attacks prompting calls of "too low!" from fans in the process. Some face punches, combined with a late left-right body blow combo, gave Corbett a commanding lead on points at the gong.[17][48][47] Fitzsimmons apparently suffered a dislocated thumb during this round and so would be required to hide this for the fight's remaining duration.[62]

Round 3 witnessed a more confident champion spearheading his campaign with a left stomach shot. In contrast, Fitzsimmons' retaliation was without method and Corbett punished this with a second powerful left stomach punch, leaving a visible red blotch on his opponent. Corbett landed more body blows but was subsequently hit by a right blow to the ear. Several clinches soon emerged; the first saw Fitzsimmons land a left head swing, but the second had the champion succeed with a right jaw punch. Corbett exploited Fitzsimmons' clinch attempt with two body blows and two right face punches. However, Fitzsimmons countered with a left hook to the jaw, to thunderous audience reception. He followed that up with a right body blow and a left jaw hook but was saved by the bell when he proved defenceless against a retaliatory punch.[17][48][47] The post-round laughter ended in Round 4, with neither boxer landing their first strikes. However, Corbett soon found accuracy with right body and jaw shots. A left swing to the jaw by Corbett was met by inaccurate retaliation attacks, allowing the champion to land some powerful punches to the face and ear. Several clinches resulted in no attacks on the breakaway, Corbett having reportedly held on to regain his strength. Fitzsimmons absorbed more facial punishment and technical body blows from both sides. However, one face punch caused Corbett to bleed. Undeterred, Corbett undertook a more aggressive approach to his body blow plan, with his strikes giving him back the points lead upon the round's conclusion.[17][48][47] However, he too had injured his left thumb during this period.[62]

Corbett began Round 5 with a hard left jaw shot, while his footwork prevented Fitzsimmons from forcing him into a corner. An exchange of right body blows was followed by a jaw-stomach combo by Corbett and an uppercut during a clinch. Fitzsimmons responded with a right hook to the jaw and a blow under his foe's chin. However, a blow from Corbett split Fitzsimmons' upper lip and damaged his nose, the audience again erupting at the bloodletting. Corbett capitalised with some powerful rights and lefts to the head but was forced to clinch upon a right swing to his ear. Two left hooks to the jaw caused Fitzsimmons to bleed more profusely and it became clear he was suffering from fatigue. Corbett therefore was able to land consistent attacks without threat of retaliation, particularly to the head.[17][48][47] In Round 6, Fitzsimmons was on the offence with swings to the jaw. He received a caution from Siler for roughing during an attempt to wrestle Corbett onto the ropes. This forced a more cautious approach from the challenger, allowing Corbett to land a right hook, a right swing to the ear and a left to the face, consequently increasing the bloodletting. Fitzsimmons was now struggling to breathe; Corbett's right jaw hook and left swing were enough to bring his opponent down. Siler counted as Fitzsimmons was on his knees, though Corbett accused the referee of doing this too slowly. Fitzsimmons, despite some Corbett fans insisting otherwise, got up at nine. Despite being groggy at times, he withstood Corbett's offence until the time expired.[17][48][47]

During the count, Corbett had grinned at Rose, but she responded "Oh, you can't lick him".[63] Mrs Fitzsimmons' resolve gave new motivation for her husband, now keen to subsequently lick Corbett for his blatant disrespect towards her.[63] Thus, Fitzsimmons was somewhat refreshed in Round 7, but not for long as Corbett landed a left hook to the jaw and a right body blow. Three consecutive jabs from Corbett saw blood spill across both boxers, Corbett now having aimed for shots to Fitzsimmons' wounded mouth. Fitzsimmons missed right shots to the jaw and the subsequent clinching saw the pair receive cautions from the referee. A right from Corbett landed with some power, but the challenger's punch to the head proved more impactful. Both exchanged jaw hooks with Fitzsimmons landing a right uppercut, though he certainly looked worse for wear as the round headed to its conclusion.[17][48] In Round 8, Fitzsimmons blocked Corbett's left hook but his combos failed to hit the target. He then hit a heavy left hook, but Corbett dodged a follow-up and countered with some left stomach blows. Fitzsimmons' hard left blow was limited by Corbett having drawn himself back, where the champion's follow-up lefts to the jaw caused Fitzsimmons to bleed once more. Further damage was inflicted on his nose, including via a left hook right before the gong. Fitzsimmons's bloody sight meant his attempts to reassure his wife failed. However, his strength and resilience were noted by the crowd, prompting some to bet late on for an upset victory.[17][48]

Round 9 began with long-range attacks, Corbett gaining the upper hand. Fitzsimmons therefore insisted on close-range fighting; he landed a left hook to the chin but received lefts to his jaw and face in return. A clinch enabled Corbett to land a punch near Fitzsimmons' heart, but he was soon staggered by a powerful Fitzsimmons' left hook on the third attempt, a punch that delighted the audience. A follow-up stomach shot was too below the belt for Siler's liking, who promptly gave Fitzsimmons his third match caution. The fight again became close quarters, but this time Corbett successfully landed a left jab and an uppercut. However, again on the third attempt, Fitzsimmons struck Corbett with a devastating right body blow, followed by a left swing to the jaw. Though heavily-breathing post-round, Fitzsimmons' confidence had grown while Corbett's focus reportedly decreased.[17][48][47] Round 10 saw Fitzsimmons begin as the aggressor; though Corbett avoided a left swing, he failed to stop a hook to the jaw during a clinch. Fitzsimmons had also begun to deliver powerful body blows, including a right to the kidneys and a left stomach blow. These in turn enabled Fitzsimmons to land a hard left to the jaw. His confidence waning, Corbett became ever so more aggressive and landed several left-right shots, which again caused blood to pour. Despite this, Fitzsimmons remained defiant and delivered three lefts to Corbett's head. This only enraged the champion further; after receiving a right hook to the ear, Corbett landed a right body blow and a left hook to the jaw, which the crowd certainly appreciated. However, The New York Times reported Corbett no longer boasted his "confident smile" post-round.[17][48][47]

A shift in Fitzsimmons' fighting style also emerged.[59][17] After hearing his wife's advice ("Hit him in the slats, Bob!"), he now focused on the champion's body.[59] In Round 11, Fitzsimmons again initiated the battle, though Corbett counted with left jaw hooks. After his lefts to the jaw were neutralised by Corbett's left ear strikes, Fitzsimmons controlled proceedings with a powerful right body blow and one to the head. Neither hit saw any retaliation, though Fitzsimmons' attempt for a knockdown was well-scouted by the champion. However, Corbett began to initialise clinches as fatigue set in. This allowed Fitzsimmons to land several rights to the champion's jaw, followed up with a uppercut. Two left chin hooks then emerged, followed by another late barrage of left jaw hooks and right body blows. Rose cheered throughout it all, as did many of Fitzsimmons' backers. Corbett was forced to clinch to survive the round.[17][48] In Round 12, Fitzsimmons' charge failed as did Corbett's retaliation. Corbett slammed a left to the damaged nose followed by a left jaw hook post-clinch. After Fitzsimmons missed left and rights, Corbett forced him into a corner where he delivered rib blows and a left hook. He followed it up with four unretaliated lefts. Fitzsimmons then fought back with a right hook and an uppercut, before adding a left body blow post-clinch. But during a second clinch, the champion came exceptionally close to landing a powerful KO-potential right-hand uppercut, but just barely failed to hit his foe. Fitzsimmons was bloodied and fatigued as the round ended.[17][48]

Fitzsimmons was nevertheless fresh enough for Round 13. An early attack crucially hit one of Corbett's gold teeth, causing it to become loose. Both men then exchanged left-body blows, but Fitzsimmons also delivered two powerful right ones. Corbett responded with a left hook and body blow before he countered a Fitzsimmons charge via a right uppercut. But the damage to his tooth was too much, forcing the champion to spit it out. Corbett then ducked a barrage of Fitzsimmons attacks, responding with a punch to the nose. However, Fitzsimmons retaliated via a powerful right to the ribs. A right jab also dislodged another of Corbett's teeth, which ended up in the ringside seats. Corbett responded with a chin shot and a left body blow but was then hit by a right uppercut. Fitzsimmons was bleeding through his nose again, which Corbett tried to damage further with a left jab. Post-round, The New York Times remarked that the champion appeared more fatigued than the challenger was.[17][48]

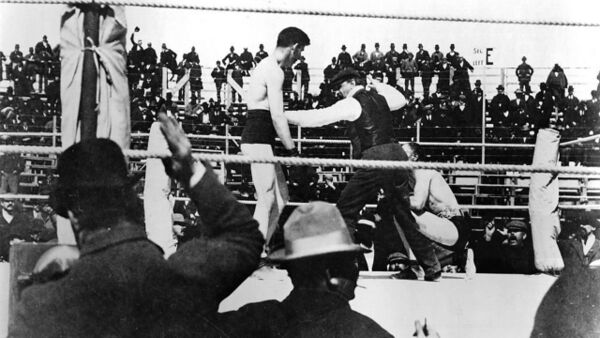

In Round 14, Corbett started as the aggressor. He missed his right hook but landed a left to the jaw, which prompted Fitzsimmons to deliver a right hook to his foe's head. Two jaw hooks were followed by a left uppercut from the challenger, which The New York Times remarked appeared more damaging than Fitzsimmons' earlier attacks. Then, the famous moment occurred: Fitzsimmons goaded Corbett by attempting a low-powered right hook. The champion was tricked into throwing his back and chest in anticipation, crucially exposing his stomach. Without hesitation, Fitzsimmons landed the "Solar Plexus" blow.[64][14][2][59] It knocked back a stunned Corbett and Fitzsimmons finished him off with a right hook to the jaw. The knockdown was achieved, but Corbett was notably still conscious. Once Fitzsimmons retreated to his corner, Siler began the count. Alas, Corbett, despite technically having fifteen seconds to do so, lacked the strength and struggled to breathe, as he grasped his heart. Thus, he could not answer the ten-count; while some Corbett fans cried "Foul!", Siler had none of it. It was a fair knockdown and Fitzsimmons was subsequently declared the victor.[17][48][47][12] With this, a new undisputed World Heavyweight Champion had been crowned.[10][17][14]

Post-bout, after being helped up by his entourage, a hysteric Corbett approached Fitzsimmons and begged for a rematch.[48] Upon being declined, the incensed former champion charged at Fitzsimmons, breaking through the seconds who tried to stop him.[65][48][17] Fitzsimmons blocked and ducked Corbett's initial attacks, with the pair ending up in a clinch.[48][17] Ultimately, a right jab was too weak to trouble the new champion, who understood and empathised with Corbett's current mental well-being.[17] Corbett was taken by his manager William A. Brady and his other seconds back to the dressing room.[48] Brady then returned to insist the match continue.[65] After that failed, he demanded a rematch, insisting that Corbett could pick up the victory and a $20,000 purse.[48][17] Alas, Fitzsimmons et al were uninterested.[48]

In his dressing room, Corbett completely broke down in tears; he accepted Fitzsimmons had won cleanly but insisted he should have won, especially if he had a few more seconds in Round 6.[17][48] He was also devastated that he cost his friends, as well as his brothers Harry and Joe, thousands in lost bets.[48] Likewise, his family deemed his focus on a budding acting career as the catalyst for his downfall.[66] Brady believed his fighter was suicidal following the fight.[65] Meanwhile, Fitzsimmons performed a celebratory dance, where he was greeted by Rose.[17][48] Bob's condition meant little to the pair, who passionately embraced before they returned to his dressing room.[17][48] The New York Times estimated Fitzsimmons would make around $50,000 for his victory, associated bets and other moneymaking schemes.[17] More money was soon to arise with the upcoming film's release.[49] Bright estimates he and Corbett made about $44,000, subsidised by $20,000 from external sources.[65]

In a post-match interview, Fitzsimmons hailed Corbett as the most intelligent man he had ever met, where he explained that his game plan involved wearing down his opponent over time before landing a KO blow.[17] He also admitted that the blow which split his lip gave him the most consternation.[17][47] Months later, Fitzsimmons claimed his wife played a major role through her defiance of Corbett's mind games and for her advice to "Hit him in the slats!".[63][59] The New York Times declared the bout a "great contest", praising the boxers for engaging in a clean, "purely scientific" fight.[17] In his report for The New York World, Earp deemed the bout to be "the greatest fight with gloves that was ever held in this or any other country".[54] The bout did garner some controversy, however.[54] It mainly surrounded whether Fitzsimmons took too long to get up in Round 6, as well as if his final punch to the jaw was fair considering it appeared Corbett was already on his way down to the mat.[54][65]

The Film

The bout's elaborate film production has its roots dating back to 1894.[67][49] Enoch J. Rector, alongside the Latham brothers (Grey and Otway) and Samuel J. Tilden, decided to establish the Kinetoscope Exhibition Company after seeing potential in Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope.[68][67] They identified a legal loophole: because of the lack of film legislation, recordings of prize fights were perfectly lawful.[49][68] With this, the company worked with William K. L. Dickson so that the Kinetograph, which previously was capable of capturing 20 seconds of footage, was now able to record a minute.[49] Boxers Michael Leonard and Jack Cushing were then filmed in a "bout" lasting six rounds.[49][67] The production, titled Leonard-Cushing Fight, was released on 4th August 1894 and screened on a Rector-Latham Kinetoscope that now boasted 150 feet of capacity.[67][49][68] Alas, the film was not a major hit primarily as neither boxer was especially well known, as well as the fact most customers were only interested in seeing the final round.[67] It also landed Edison in hot water with New Jersey investigators concerned about whether the contest was a prize fight.[67] Ultimately, Edison faced no charges.[67]

Still, Leonard-Cushing Fight generated sufficient revenue needed to justify a second experiment.[68][49] This time, the Kinetoscope Exhibition Company landed a major coup when Corbett agreed to terms on an exclusive film contract.[23][49][67] The company's hopes to film a possible Corbett-Jackson fight was shot down when the world champion opted to maintain the color bar.[67][20] However, another account suggests manager Brady reportedly turned down $15,000 and instead demanded $25,000 should a fight emerge, where negotiations broke down.[69] Regardless, Corbett did agree to fight the "New Jersey Heavyweight Champion" Peter Courtney in six one-minute rounds for $4,750, Courtney having apparently gained sufficient credentials due to a previous fight against Fitzsimmons.[67][69][49] Thus, Corbett and Courtney Before the Kinetograph was released on 17th November 1894 to significant success thanks to Corbett's notoriety.[67] The champion and Brady both received extensive royalties, Corbett having earned $20,000 from the film alone.[67][68] It also increased Corbett's reluctance to defend the belt, since his acting career had already begun to challenge the money he earned during his boxing career.[23]

There were two main limitations with these early films: they were choreographed and rounds could not last beyond a minute.[49] As legitimate prize fights would now last three minutes per round under the Marquess of Queensberry rules,[40] a new camera would be required as the Kinetograph was modified to its limit.[49] During these developments, Grey Latham offered $50,000 to film a bout between Corbett and Fitzsimmons prior to 1st November 1895, providing the weather was sufficient.[24] Grey even insisted they could fund this without the requirement of ticket sales, having foreseen the work's lucrative possibilities.[24] Alas the death of Riordan ended those plans for the time being.[23][24][14] During this time, there was infighting within Kinetoscope Exhibition Company, as Rector and Tilden became concerned with the Lathams' poor business practices.[42][49] When the dust settled, the Lathams' Eidoloscope Company was forged, while Rector assumed complete control of the Kinetoscope Exhibition Company, which crucially retained exclusive filming rights for Corbett's future appearances.[42][49][23] Once this split occurred and Fitzsimmons' legal troubles ended, Rector also got Stuart and Fitzsimmons on board with the deal and plans quickly emerged to record the entire fight set for 31st October 1895.[23][34] Sources conflict on what cameras Rector planned to utilise.[42][23][49] A Million and One Nights: A History of the Motion Picture and Fight Pictures claim that thanks to Rector's connections with Edison, he was able to use four Kinetographs to capture the fight.[42][23]

However, research from Bright Lights Film Journal indicates Rector had loftier ambitions.[49] Frustrated with the Kinetograph's limitations,[42] where continuous recording for more than a minute would snap the film, Rector opted to establish a massive wooden building that housed all the necessary camera equipment.[70] Crucially, this camera, coined the Veriscope, could be fully monitored by its crew, thus preventing any chances of the film being torn apart.[49][70] For this new project, Rector and Stuart established the Veriscope Company, with about $860,000 in investment.[71][49][42] Alas, this contest would have to wait following the Texas and Arkansas fiascos, combined with Corbett's "retirement".[9][27][29] Instead, plans emerged to film the second Fitzsimmons-Maher fight.[5][42][23][49] Because of the outrage in nearby Texas, Rector worked against the clock in secret to establish a makeshift arena as well as a necessary bridge across the Rio Grande.[42][23] During this, he encountered the charismatic Judge Roy Bean and his henchmen, who pointed out the legal issues of the bridge's construction.[72][42] Bean was placated when Rector offered him a place in the New York film industry, where he also decided to help promote the match.[42][72]

Alas, while the bout took place, the recording of it was thwarted because of rainy and overcast weather.[5][49][42][23] This prevented adequate sunlight needed for the Veriscope's Blair film, making it impossible to capture quality footage.[49] Despite urges to delay the bout, this could not be done thanks to the rowdy crowd and the fact both American and Mexican officials were trying to put a stop to the proceedings.[23][42][72] Whether Rector tried to commence filming anyway is unknown, but most sources agree the resulting footage would not have been suitable for theatres.[5][23] A backup plan, where Fitzsimmons and Maher would conduct a six-round choreographed fight, also came to nothing when an already reluctant Fitzsimmons demanded between $5,000-$10,000 upfront plus half of the work's revenue.[23][54][24] However, thanks to Corbett's "unretirement",[3][27] a far more lucrative opportunity arose: the first World Heavyweight Championship bout to be captured on film.[73] The original negotiations for the Corbett-Fitzsimmons bout were initially agreed upon in September 1896 and finalised by 17th December that same year.[39][17]

However, the original fight date of sometime in January 1897[39] never materialised as Fitzsimmons had blown a gasket when he reviewed the film contract.[42] It declared that whereas Corbett and Brady would receive a quarter share of the revenue, Fitzsimmons and Julian would only get $13,000.[42] Having refused to fight until this was rectified, negotiations continued up to 4th January with Julian demanding a third of the film's revenue.[41][42] Eventually, a deal was made where the boxers both received an equal share.[42][54] A Million and One Nights claimed Corbett and Fitzsimmons would earn a quarter of the spoils,[42] but other sources suggest they only received 15%.[74][54][50] Regardless, the bulk of the revenue would supposedly be shared between Rector, Tilden and Stuart.[42][50] Crucially, Stuart would be in control regarding the film's release and allocation of revenue, meaning the boxers et al were dependent on both his ability to promote the match and his word.[41][65] The deal also allowed Brady to become the film's producer.[75]

During these negotiations, Rector continued the Veriscope's development, utilising a more compact version to film productions like a documentary on the Newark Fire Department.[42][49] Aside from additionally increasing its reliability and speed, Rector supplied it with 63mm nitrate film produced by George Eastman after Stuart acquired a 600,000-foot deal in exchange for $140,000.[49][71][42][50] Boasting a 1.65:1 aspect ratio,[75][23] it was one of the first cameras capable of capturing widescreen footage.[49][50][42] Widescreen (and wide-film) was in its infancy, with pioneer British filmmaker Birt Acres having harnessed a 70mm camera to capture wide-film footage of the 1894 Henley Royal Regatta.[76] Some "widescreen" productions had also been screened on the Lathams' Ediloscope by 1895.[77] Hence, Rector's Veriscope was a culmination of widescreen's development and was expected to capture a significantly longer film than those that preceded it.[49][50] Like the Lathams' Eidoloscope camera, the Veriscope also contained the Latham Loop, which prevented excessive stress from snapping the film and thus allowed longer recordings.[55][49] Suddenly, the limitations of the Kinetograph era no longer applied.[49][42]

Rector also established his own projector for this endeavour.[78][49] Prior to the second Fitzsimmons-Maher fight taking place, film projection was still in an experimental phase,[79][49] Rector had intended to maximise the Kinetoscope's capabilities via a custom-made device which could enable five people to view the footage simultaneously.[49] But with the increased adoption of film projectors like the Vitascope and Mutoscope,[79][76] Rector's Kinetoscope became obsolete before it was even made.[49] Instead, Rector created a projector capable of displaying 63mm footage, which he also coined the Veriscope.[78][49] There were likely two other main reasons for this unique projector's creation: Firstly, to avoid scrutiny over whether the projector violated Edison's 35mm Kinetoscope patent;[80] and secondly, to combat against the growing problem of piracy.[78][42] Concerned about the simpleness in stealing a production, Rector made sure to establish an exclusive contract for this fight.[49] Copyright notices were also placed on the ring skirts,[23][50] while it was made strictly forbidden to carry a camera into the Race Track Arena.[49]

Once Carson City agreed to host the occasion, filming preparations were in full force.[23][54] As with the Fitzsimmons-Maher contest, a wooden structure was created to house three side-by-side Veriscope cameras.[23][77] The logic behind this was the Veriscope could capture eight minutes of film before they needed a replenishment.[49] Because of this and the desire to capture the fight's prelude and aftermath, Rector initially had his cameras begin capturing footage in four-minute intervals.[49] Hence, when a camera required its replenishment (or in the worst case, malfunctioned), two other cameras would actively record the bout to ensure nothing bar a few jump cuts were ultimately lost.[77][49][54] The 63mm format also enabled the cameras to be up closer to the action while still being able to cover the whole ring.[49] Or at least, that was possible with a modified 22-square-foot ring as requested by Rector and Stuart.[23][54][50] However, referee Siler noticed the alteration and ordered the ring be reverted to its original 24-square foot size to avoid possibly tampering with the fight's outcome.[23][54][50] The problem was that not all areas from the corners could be seen from the cameras' field of view, which meant Corbett's knockdown could not be fully viewed once he crawled to a nearby corner.[23] But aside from this, the cameras were given the best view possible.[49][23][77]

A few contingency plans were also put in place.[23][54][42] The Smith-Green and the Hawkins-Martin matches were booked by Stuart, not just to entertain the crowd before the main event, but also to give more time for ideal filming conditions to arise.[54][48] This move, obviously conducted following the Fitzsimmons-Maher non-starter,[5] proved a wise decision.[54][23] Even as the main event quickly approached, the sunny conditions forced Stuart to further delay it so that the Veriscopes could capture quality footage.[23] Rector also transported 48,000 feet of film in anticipation of a long-fought contest.[42] In fact, the long fight "expectation" may well have been guaranteed before the fight.[23][50] One long-standing rumour, initially raised by the San Francisco Chronicle, was that the two boxers agreed to keep the fight going for at least ten rounds so that adequate footage of their contest could be captured.[23][50] This has never been conclusively proven, though if it was indeed true, it could explain why Corbett ultimately did not secure a KO in the sixth round.[23][50][17] In total, between 11,000-12,600 feet was captured.[49][23][50] This included the whole bout, as well as footage of former Sullivan and his manager Billy Madden, Siler, the full pre-fight entrances and ten minutes of the crowd post-bout.[24][77] The raw footage lasted almost two hours, a record for the era.[50][23][42]

The contents were kept under lock and key in New York.[49] Even before the bout emerged, Congress, led by J. Frank Aldrich, had already debated the ban of prize fight pictures and descriptions.[23][24] A vote was called on 1st March, but the proposed bill failed to achieve consensus because opposition argued it would have forbid the media's crime reports.[23][24] Subsequent debates after 17th March also failed to make prize fight films illegal; this included state legislation attempts, which may have been thwarted thanks to bribes from Stuart.[23][54][24] In the meantime, Rector and Stuart repeatedly informed the media that the bout's recording was a complete disaster, having contained far too many defects for it to be watchable.[81][24][54][49] In actuality, the recordings were mostly pristine, though Brady claimed in his book The Fighting Man that the cameras missed the solar plexus punch.[24][65] Rector preserved one uncut copy while he edited another containing the best quality footage.[49] Most sources state the edited film lasted about 100 minutes.[54][50][77] However, Bright Lights claims it was originally edited down to 75 minutes.[49] It is likely the full version was not originally showcased in its premiere.[54] Particularly, The Emergence of Cinema found an April 1898 showcase of the film in Boston was among the first to contain the bout's aftermath.[54] Irrespective of the film's actual run-time, it is objectively considered the first-ever feature-length production.[49][23][50]

The film was finally ready for the public by May 1897.[54][49][42] Its premiere was at the New York Academy of Music on 22nd May, the first time this opera house had showcased a film production.[42][54][24] The film was split into six reels containing up to four rounds each, forcing a delay of five minutes as the reels were replaced.[54][49] The sold-out audience, who acquired a 25-cent gallery seat upwards to a $1 orchestra placement, were nevertheless highly engaged with the bout before their eyes.[49][54] The film also heralded the introduction of sports commentators, who summarised key details including the important sixth and fourteenth rounds.[27][54][49] Brady recalled using this to try and convince the public that Fitzsimmons' win was illegitimate.[65] Particularly, during an Academy of Music showcase, Brady became the commentator and had the film deliberately slowed down to "prove" Fitzsimmons was down for thirteen seconds in Round 6.[65] However, the match referee (who Brady claims was not Siler but Muldoon) came out and insisted Brady was lying.[65] Alas, Brady's efforts, as well as others who tried to claim Fitzsimmons' final punch was illegal, did nothing to change the match's outcome in the public's eyes.[65][54][71]

The work's Academy of Music premiere lasted about five weeks and it often achieved sell-outs of the 2,100-seat building.[54][49] Soon, with the help of eleven contracted companies, the film reached other large American cities like Boston and Chicago.[54][24] To avoid any further bad publicity, the first advertisements omitted the word "fight".[49] This instruction was seemingly relaxed the following year, as an 1898 promotion by the Police Gazette explicitly referred to it as "the great fight".[82] These steps did little to placate some states, with Iowa among those to prohibit the film's circulation.[54] Nevertheless, the film soon embarked on an international tour.[54][49][65] Its first overseas stop was the Little Theatre in London on 27th September 1897.[83][54] Such was its compelling nature that even the Prince of Wales was reportedly interested in seeing it, which prompted Stuart to consider opening a private venue for the future King Edward VII.[84] Another historic destination was Dublin in April 1898, making it the first US feature film to be screened anywhere in Ireland.[85] The film likely made history in other countries; according to Brady, it reached Australia, China, Egypt, India, Japan and South Africa.[65][49] Canada and France also received releases in Toronto and Paris respectively.[86]

For its domestic release, The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight received an enthusiastic critical reception.[71][49] In Chicago for instance, the Grand Opera House received a sold-out attendance who were able to relive the match experience.[87] A similar positive account was reported at Milwaukee's Davidson Theatre.[86] In Boston, in part thanks to replacement high-quality film for Rounds 11-14, saw thunderous applause for the bout's key moments, something reflected in Atlantic City's States Avenue Opera House premiere.[86] The premiere at the Toronto Opera House was so greatly received that spectators went as far as to cheer the House's managers, W. Clifton Turner and Ambrose J. Small.[86] Notably, Sir Oliver Mowatt had attempted to produce a bill to outlaw the film across Canada.[88] Alas, a Senate hearing in Ottawa rejected it in June 1897 for the same reasons as Aldrich's, mainly that it would prevent newspapers from publishing prize fight reports.[88][23][24] The Phonoscope's subsequent July 1897 report in Toronto remarked there were no signs of anything offensive throughout the screening.[86]

In fact, the only criticism the film received surrounded technical limitations and poor operation by theatres that screened it.[89][49] The San Antonio premiere for instance was a complete faux pas because the coincidentally named Grand Opera House's operators failed to get the projector to function, blamed on an "ill" operator and a troublesome new machine.[89] Irked attendees demanded their money back, with some violent scenes having consequently occurred because the House's management insisted on merely returning the tickets instead of giving out refunds.[89] The police were called to deal with the unrest.[89] Some other enthusiastic viewers also reported eyestrain after long-term viewing, presumed to be the consequence of a mere 30-foot display.[49] The film subsequently became a major commercial success, with its final notable showcases being in 1900.[54][49][27] The film is typically estimated to have reached roughly $750,000 in revenue,[27][23] but Bright Light Film Journals claims it was close to breaking the $1 million mark.[49] When deducting the initial $46,000 production budget plus other expenses like transportation,[71] the film made over $120,000 in profit.[54][27] Such was its dependability that the Jonah Theatre in New York City decided to screen the film for its relaunch.[90]

However, more shenanigans would arise regarding the bottom line.[91][54][49][51] According to Brady, Stuart had taken over Veriscope as its president and instilled his brother as the treasurer.[65] However, Rector claimed he and Stuart were business partners, who had verbally agreed to allow the former to receive 25% of the film's revenue.[91] The lack of a tangible contract proved a major mistake for this engineer, as he essentially depended on Stuart's word when it came to receiving any financial compensation.[91][49][65] After receiving no money for nearly two years, Rector approached Stuart to demand at least 15% of the revenue.[91] Stuart responded that he only promised to pay Rector provided the film made a net profit and there was none to offer.[49][91] In July 1899, Rector took legal action against Stuart after the latter admitted the film actually made over $120,000.[91] Alas, Rector barely made anything from this lucrative production.[49] Though Rector and Brady claim the boxers received around $60,000-$80,000 each,[91][65] Corbett also took legal action against Stuart as he too believed he was not properly compensated.[51] The only individuals seemingly happy with the deal were Fitzsimmons and Julian, who had received two $10,000 film royalty cheques by December 1897.[74]

Since the film's release, it has been subject to extensive analysis and commentary.[23][24][77] Some of it reflects filmmaking's infancy, including how the audiences typically reacted with amazement upon seeing a man light a cigarette with such clarity in Round 8.[49] Others have attempted to explain an interesting phenomenon; during the film's premiere in various American cities, it was not uncommon to see a sizeable female representation.[56][24][54][23] Particularly, Milwaukee and Atlantic City's premieres contained a vast number of female attendees,[86] while a Chicago showcase reportedly saw three-fifths of the audience be women.[87][56][54][24] Media reports initially dismissed the trend as women deliberately seeking to be appalled and terrified by the film's contents.[54] But modern studies have interpreted things differently.[56][24][54] For example, Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film noted women were typically forbidden from attending prize fights, be it legally or from cultural stigma.[56] But women faced no such barriers upon the film's release, with middle-class young women particularly taking advantage of the independence they often seldom received.[56][54]

However, another aspect, theorised extensively by Babel and Babylon and Out of Bounds: Sports, Media and the Politics of Identity, concerns the "forbidden" nature of seeing the partially naked and well-groomed bodies of the competitors in action.[24][56][54] Particularly, Corbett was frequently cited as being good-looking and also a "ladies' man" of his time.[92][93][24][77] Though not acknowledged by Victorian-era publications, Corbett's shorts are considered remarkably revealing, even in modern times.[24][49][77] The presence of Corbett's near-naked, buttocks-exposed body has led some to ponder whether this was the key catalyst towards the film's surprising appeal to women, rather than the fight itself.[24] That being said, The Phonoscope's Atlantic City report claimed the female audience was also keen to see Corbett win and were somewhat disappointed when Fitzsimmons picked up the victory.[86] This may explain how later boxing films, which typically did not feature Corbett, suffered a major decline in female attendance going forward.[54][93] However, Out of Bounds also acknowledged that Veriscope made several hyperbole claims during its promotions, which likely extended to its claims on the presence of female attendees too.[24]

Objectively, the film is cited as among the most important to ever be produced.[94][23][50][49] In the world of boxing alone, it is among the earliest films of the sport and the first heavyweight championship clash to be recorded.[7][73] But for the film industry, it is a cornerstone as the first feature-length production and the inaugural "true" widescreen work.[94][50][49][23][75] It is also heralded as the first film to appeal to a more general and somewhat lower-brow audience, something that has generally stuck with the film industry ever since.[94][42] It and other subsequent early boxing films are cited by Cinema: The Beginnings and the Future as having paved the way for cinema itself to thrive.[94] Among these include The Fitzsimmons-Jeffries Fight, the next World Heavyweight Championship match to be filmed courtesy of the American Vitagraph Company.[95][27] The work represented the fragile nature of early filmmaking; the match could not be adequately recorded due to the lack of artificial light, forcing a "reproduction" to be established instead.[27] Such was The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight's influence on the filmmaking industry that it was inducted into the National Film Registry in 2012.[96][97] It was surprisingly not the first boxing film to enter the Registry, as Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest was inducted in 2005.[97]

Reproduction of the Corbett and Fitzsimmons Fight

Even back in the late 1800s, film piracy was still considered a major threat.[42][54][94] It ultimately became a wise decision for Veriscope to secure exclusive filming rights, as other filmmakers were also keen to capture the bout.[49] For instance, Acres was rumoured to have seriously considered recording the bout.[98] However, while he had a cameraman in America, any chances of filming the bout legally were scuppered when Acres discovered Veriscope's exclusivity clause.[98] Cameras of any kind were strictly forbidden outside of Veriscope's.[49] However, while no unauthorised footage is known to have been captured, teenager Hugh Castle was able to smuggle in his Kodak and snap two shots of the event.[49] Paranoid about possible piracy, Veriscope reportedly paid almost $25,000 to file copyright notices worldwide, which mandated that multiple copies be sent to Washington, the United Kingdom, Canada, France and Germany.[99] The company also planned to deliver copies to every state upon the film's release, even though it took a day just to produce one copy.[99]

The April 1897 issue of The Phonoscope speculated that most pirates would deliberately mislead viewers into seeing copies of Corbett and Courtney Before the Kinetograph, by labelling their "works" as being footage of the Corbett-Fitzsimmons bout.[99] However, one filmmaker was still keen to capitalise on the fight's lucrative nature in a more elaborate way: Siegmund Lubin.[100][54] Lubin entered the filmmaking market in 1896 with the Cineograph.[101][100] By May 1897, he had begun to produce his own films.[100] Having assessed the publicity of the upcoming film featuring Corbett and Fitzsimmons, Lubin discovered that while filming the actual bout was legally out of the question, nothing was stopping him from recreating it.[102][54] Armed with this simple if highly unethical premise, Lubin set about filming his "reproduction", using conventional 35mm film.[54] As the actual boxers agreed to an exclusive contract with Veriscope,[41] Lubin enlisted two Pennsylvania Railroad freight handlers to become "Corbett" and "Fitzsimmons", where they would engage in a bout as described by newspaper accounts.[54][42][101] The "contest"'s fourteen rounds were filmed on a rooftop studio, though to save money and film stocks, Lubin opted to film the occasion at a low framerate and reduced overall round time.[54] In total, 700 feet of footage was captured.[54]

Whereas The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight underwent a slow and delicate editing process,[49] Lubin's work, titled Reproduction of the Corbett and Fitzsimmons Fight could be released almost immediately.[54] Initially released in Philadelphia,[42] the film quickly went to Chicago, Little Rock and Elizabeth, New Jersey, with seats ranging in price from 10 to 50 cents.[89][103][54] Naturally, cinemagoers were heavily displeased to witness rounds that barely went ten seconds on screen, with the actors failing to replicate the technical mastery on display in the original fight.[89][54][17] "Fitzsimmons" was noted as having clearly worn a wig, while the referee was described as "a tall man in a yachting suit".[103] Rounds 1 and 14 were also cited as being especially unconvincing when it came to making the fight appear anything close to legitimate.[89] So outraged with the fake film on display that everyone who attended the Little Rock showcase had left by Round 3.[89] Most charged towards the box office to demand full refunds.[89] Eventually, theatre manager Roy I. Thompson allowed Senator Worthen to refund the $253 to the patrons.[89][54] The resulting scene almost caused a riot and a human crush as people desperately attempted to get refunded first.[89]

Violent scenes also unfolded in the Lyceum in Elizabeth, forcing twenty police officers to calm the situation.[103] Manager A. H. Symonds was sympathetic to the situation and issued full refunds.[103] His Chicago counterpart was not, having deemed the patrons "lobsters" for thinking a 10-cent production was the real deal.[89] The Park Opera House premiere in Jacksonville was a disaster, mainly because the theatre's operators inexplicably repeated the footage of Round 1 for Rounds 2 and 4.[104] The irritated crowd became more outraged when the theatre's Projectoscope malfunctioned and would not be repaired until two weeks later.[104] Confirmation of this being a Lubin showcase was achieved when the June 1897 issue of The Phonoscope described the "Fitzsimmons" actor as looking "mightily like a made-up 'Bob'".[104]

Lubin's trickery was so far-reaching that Veriscope filed for legal action on theatres and other buildings it believed had violated its copyright.[105] But ultimately, there was little Veriscope could do against Lubin, as he technically did not violate any copyright laws.[54][42] Despite frequent refunds, Reproduction of the Corbett and Fitzsimmons Fight was still profitable,[42] convincing Lubin to produce further re-enactments.[106][54][102] He actually beat Vitascope in producing his own "reproduction" of the Fitzsimmons-Jeffries bout,[27] while his re-enactment of the Jeffries-Sharkey match contributed greatly to the bout's filming controversies.[107][106][102] It led to Lubin being declared the "Duping King" and an influential figure in early film piracy.[106][101][94] His practices continued for years, with him using the notoriety his "reproduction" brought during his Cineograph advertisements.[108] But in the early 1900s, Edison's legal action finally put a stop to it.[102][100]

Aftermath

To date, Fitzsimmons is considered the lightest boxer to ever win the World Heavyweight Championship.[60] Considering the bout's financial success and how it was hotly contested throughout, one would expect a rematch to have emerged.[17] Alas, Fitzsimmons was never heavily interested in defending the belt against Gentleman Jim.[109][2] After denying Corbett's immediate challenge post-bout,[48] the pair met again on 23rd March 1897 at the Baldwin Hotel in San Francisco.[62] There, Corbett accepted Fitzsimmons won clearly and demanded a rematch.[62] But while Fitzsimmons again complemented Corbett's intelligence, he and Julian insisted no rematch would emerge as Fitzsimmons had "retired".[62] Naturally, this was not the case; Fitzsimmons' first match after Corbett was a KO non-title victory against the debuting Lew Joslin on 5th June 1897.[12] On 30th December, Corbett again challenged Fitzsimmons; not only did he offer monetary rewards should Fitzsimmons accept and withstand the fight, but he also promised to retire if he lost again.[110] He later upped the pay to $35,000 providing Fitzsimmons could survive ten rounds.[111] Brady claimed that Corbett essentially stalked Fitzsimmons everywhere he went, including at the Green's Hotel in Philadelphia.[65]

Fitzsimmons dismissed these efforts, instead having his manager respond.[111] Julian stated to the press that Corbett's challenge could be taken more seriously if he defeated Maher.[110][111] The manager also claimed Corbett had been attempting to visit the champion on several occasions, having even accused Fitzsimmons of deliberately backing out of engagements to avoid facing him.[112] Julian believed another encounter would lead to an impromptu fight, where he bragged "So you may say that whenever Mr. Corbett does meet Fitz, Mr. Corbett will get the most infernal licking he ever had in all his born days."[112] One man sympathetic to Corbett's plight - and likely eyeing dollar signs - was Detroit promoter George Considine.[113] On 25th January 1898, he convinced Corbett to sign articles of agreement that challenged Fitzsimmons to a rematch, this time for a $25,000 purse.[113] Considine aimed to visit the champion on 30th January in Detroit.[113]

This also came to nothing but there was still one last hope for Corbett.[114] On 9th May 1898, Fitzsimmons agreed to both a $10,000 clash against middleweight Charles "Kid" McCoy and a $25,000 rematch for the World Heavyweight Championship against Corbett.[114] The clauses were that the matches must occur before the end of September and that a side bet of $10,000 would also be wagered.[114] Confident neither boxer would accept, Fitzsimmons and Julian bet $2,500 on that becoming a reality.[114] However, it was reported Corbett was interested and even tasked Brady to establish a $25,000 ten rounds bet.[114] Alas, neither bout took place, nor did a fight between Corbett and Maher.[12][1] One account indicated a rematch never materialised because Fitzsimmons believed he was greatly disrespected by Corbett, perhaps because of the latter's handshake refusal and behaviour towards Rose.[109][47][63] Another claimed Fitzsimmons threatened to shoot Corbett if they were involved in another altercation.[2] Regardless, Corbett decided to "retire" a second time because of Fitzsimmons' refusal.[109] He had insisted during a 31st January 1898 interview that he would only fight Fitzsimmons again and, regardless of whether it transpired, that he would now prioritise an acting career.[115] Alas, the lack of lucrative fights strained relations between Corbett and Brady, resulting in their partnership coming to an end.[65]

But again, Corbett returned to the ring for another match against Sharkey on 22nd November 1898.[109][1] Having suffered from ring rust, Gentleman Jim was outclassed by his opponent and was either disqualified for a low blow in Round 9 or because entourage member Connie McVey entered the ring illegally.[109][1] Regardless, Corbett would again be absent for over a year as it seemed his title prospects were over.[109][1] Meanwhile, Fitzsimmons controversially followed Corbett's method of retaining the belt, by simply not defending it.[116][13][12] Instead, Fitzsimmons launched his own acting career, where he starred in theatre plays like The Honest Blacksmith across the United States.[13][116] He eventually accepted a challenge from James J. Jeffries on 9th June 1899.[14][12] With Jeffries in top fighting form, twelve years younger and boasting a near-40 pound advantage over the champion, it proved too much for Fitzsimmons, who lost by KO in Round 11.[117][13][14][12]

The news prompted Corbett to contact his now-former manager Brady to demand a title shot.[109] Brady reluctantly put on the match, expecting it to be an easy victory for Jeffries.[109] The bout occurred on 11th May 1899;[1] anyone who doubted Corbett could not have been more wrong, as he actually dominated the champion throughout the first 16 rounds.[109][117] Alas, Jeffries fought back in the later rounds, where he eventually secured a KO in Round 23.[109][117][1] Meanwhile, Fitzsimmons sought to regain the belt; five victories by either KO or TKO certainly helped legitimise his challenge, which included a vengeance KO win over Sharkey on 24th August 1900.[14][12] The rematch occurred on 25th July 1902; he ultimately broke both his hands against Jeffries and was KOed in Round 8.[118][13][117][12] Post-bout, Corbett again made a subsequent challenge to Jeffries.[118] In what marked his final match, the past-his-prime Corbett lost by TKO on 14th August 1903.[119][2][1]

While officially out of the World Heavyweight Championship scene, Fitzsimmons continued his boxing career.[15][14][12] On 25th November 1903, he defeated George Gardner on points to win the World Light Heavyweight Championship, thus becoming boxing's first-ever triple crown champion.[14][13][12] He lost the belt to Philadelphia Jack O'Brien on 20th December 1905.[12] One of his last notable bouts was a KO loss to future World Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson on 17th July 1907.[14][12] His final official match was a win over Jersey Bellew on 20th February 1914.[12] Alas, Fitzsimmons struggled financially, not helped by poor investments, going through four wives and the upkeep of his two pet lions, Nero and Senator Reynolds.[13][14] He made a subsequent living on the vaudeville circuit and Broadway, while he also became an evangelist in later life.[64][14][116] Fitzsimmons passed away on 22nd October 1917 from lobar pneumonia, aged 54.[13][14] He is often ranked among the greatest boxers of all time, primarily thanks to his powerful punches and ability to beat the top heavyweights of the era.[2][14] One notable quote is linked to Fitzsimmons: "The bigger they are, the harder they fall."[14][13]

Elsewhere, Corbett continued with his successful acting career.[66][4][6] Among these include films which have also become lost media, such as The Midnight Man and Broadway After Dark.[120][121][6] His vaudeville career was also considered highly influential for the time, his acting credentials allowing him to make a lucrative living beyond what boxing could provide.[66][109] On 18th February 1933, Corbett passed away from liver cancer, aged 66.[122][4] He has since been considered the "Father of Modern Boxing" for his scientific fighting approach.[92][4] His legacy to the film industry also cannot be understated, with New Movie and Edison proclaiming him as the first true film star.[123] Corbett and Fitzsimmons were both inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.[92][64]

Veriscope's influence and legacy in the film industry, outside of The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight, was limited.[49] This was likely not helped by the actions of Stuart and Lubin, which drastically limited the company's revenue for an otherwise lucrative production.[54][49] Rector himself continued developing influential technologies for the fledgling film industry, but his ideas for dramatic films were largely ignored.[42] Rector passed away on 26th January 1957, aged 94.[124] According to Prizefighting: An American History, Stuart was seldom documented following the bout's promotion.[51] The book summarised him as an effective businessman but less so when it came to stakeholder management.[51] The state of Nevada also barely made money from the bout.[45] However, it quickly became a prominent base for other high-grossing bouts, including another "Fight of the Century" between Jeffries and Johnson in 1910.[43][45][44] The Race Track Arena no longer exists in Carson City, but a plaque was erected at the site to commemorate the fight and its legacy.[28]

Availability

Despite being a historic and exceptionally important event for both boxing and the film industry, the majority of The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight has been lost to time.[125][126][50][49] A few reasons may account for the missing footage: Firstly, like many other productions of the era, The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight was recorded on cellulose nitrate film.[55] Nitrate film has proven extensively difficult to preserve as they are not only prone to decomposition but also sources of ignition.[127] In May 1897, just before an afternoon showcase at the Academy of Music, a reel containing Rounds 3-5 combusted when somebody dropped a lit match nearby.[128] A more serious incident occurred in October 1897 when a faulty Bellview, Minnesota projector exploded, which allowed a nitrate fire to rage across the vicinity.[129] Ultimately, only a few injuries were reported despite a stampede from a panicked audience.[129] While other copies were available in both cases, it illustrated the film's vulnerability even during its premiere.[128] Adding to the problem, the film was released on six different reels, which had to be manually replaced every few minutes.[49][54] Like with the Jeffries-Sharkey Contest, it is possible later showcases condensed the film's overall runtime, by only prioritising key moments like the sixth round knockdown and the fourteenth round KO.[130]

In 1900, the film was taken out of circulation.[54] This decision further contributed to the work's deterioration, as most film companies were either incapable or were apathetic towards the preservation of their earliest works.[131] In fact, were it not for the efforts of Jimmy Jacobs and Bill Cayton, it is likely the film would almost be completely lost.[132][133][134] Indeed, both men are credited for their dedicated efforts to recover thousands of otherwise missing boxing events.[132][133] Jacobs, considered by many sources as the greatest player in handball,[132] linked up with boxing promoter and manager Cayton (who alongside Jacobs notably guided Mike Tyson to the World Heavyweight Championship) to jointly collect classic boxing films.[135][133][134] Their venture began in 1959; by the time Cayton sold the collection to ESPN in 1998 for $100 million,[133] it was estimated that up to 26,000 films had been acquired by the pair.[135] This included the entirety of Madison Square Garden's archive, which they purchased in 1974.[133] It is known that Tyson frequently watched footage from the collection in his quest to become the youngest holder of the World Heavyweight Championship.[135]

Among these included about 25 minutes of fragmented footage from The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight.[125] Throughout their association, the pair worked with the British Film Institute (BFI) to preserve the vulnerable nitrate film at its National Film and Television Archive.[125][133] To celebrate a century since its production, the BFI converted the surviving 63mm footage to a 35mm format, where it was then carefully edited and restored.[125] The restoration was showcased at the National Film Theatre's "Battles of the Century: A Celebration of 100 Years of Boxing Films" presentation on 11th June 1997.[125] Since then, between 28-29 minutes have been preserved at the BFI National Archive, New York's Museum of Modern Art and in ESPN's archives.[136][49][133] Though considered low-resolution compared to the master tapes,[49] about 19 minutes of footage was widely available on YouTube for years.[137] Other fragments have also been preserved in institutions like the Library of Congress and the National Science and Media Museum, including rare footage of the pair with their robes on pre-fight.[138][50] Some of this additional footage has also resurfaced on YouTube and has been subject to colourisation projects.[139][140]

Considering that around 75% of America's silent films are declared permanently lost,[131] it is fortunate that any footage from The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight survived.[125] Reproduction of the Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight is extremely likely to remain fully irrecoverable, under dramatic circumstances.[141][142] On 13th June 1914, the Lubin Manufacturing Company's film vault caught fire, which tore through the nitrate-based productions, triggered various explosions and set alight numerous nearby homes.[143][141][142] The aftermath resulted in almost the entirety of Lubin's earliest works becoming lost, as were many of his upcoming projects, marking one of the biggest losses in film history.[142][141] Reproduction of the Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight is among those casualties; a single still, initially declared as unidentified by the Library of Congress, has since been identified as having originated from that film.[144][101]

But there is one further media mystery surrounding this fight: the flipbooks which attempted to reproduce it.[145][144] The mystery began on 10th June 2013 when The University of Iowa Special Collections & University Archives posted a Tumblr gif that showed an old boxing flipbook.[146][144] Notably, the post claimed it was a reproduction of the Corbett-Fitzsimmons match.[146] Intrigued by this, Dan Streible of The Orphan Film Symposium contacted the Special Collections for more information.[144] They, alongside the Museum of the History of Science, provided additional images that contained clues to the work's identity.[147][144] Among these included a page that confirmed the fight was copyrighted by Gies & Co.'s Living Photographs, the company having conducted business in Buffalo, New York and Pittsburgh.[148][144] One Gies & Co. advertisement was published in The Phonoscope for its March 1897 issue, which notably contained an image of the same boxing bout, titled The Great Fight.[149][144] Its description confirms it was a reproduction of the Corbett-Fitzsimmons bout.[149][144] While it was preserved in various libraries, only a few pages were then publicly available.[144] That was until 16th March 2021, when Stephen Herbert of The Optilogue revealed he possessed a copy of The Fight and uploaded it to YouTube.[150][145] He also confirmed that a second part, appropriately titled The Finish, also existed, though he does not possess a copy of that flipbook.[145] Both films contain credits to an as-yet unidentified individual known only as M. Kingsland.[145][144]