The Burns-Johnson Fight (partially found footage of boxing match; 1908)

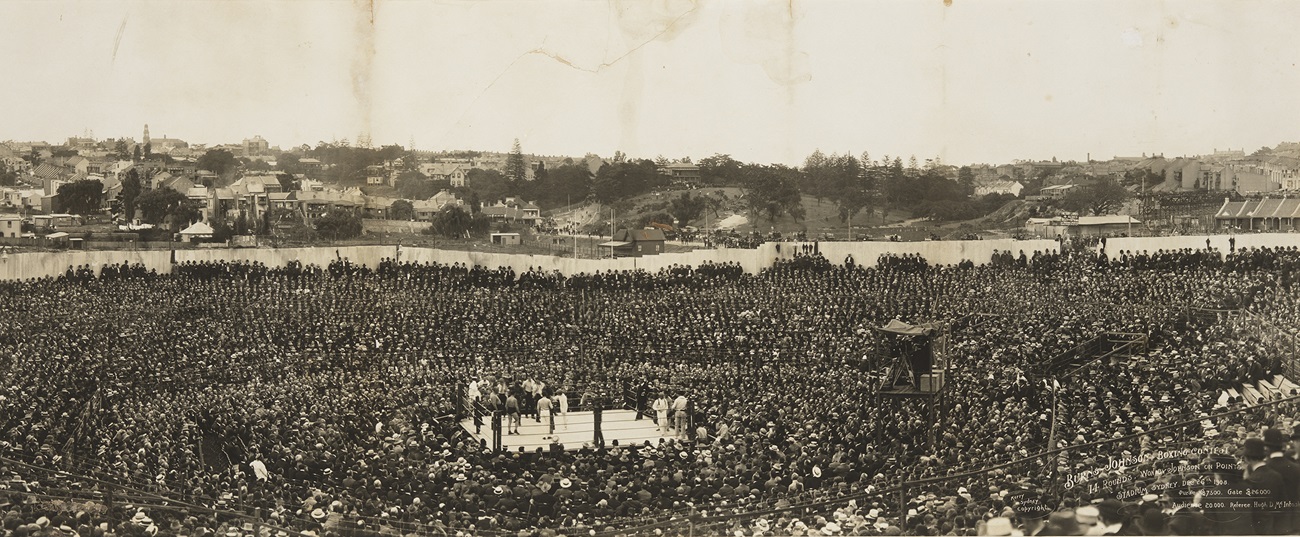

Kerry & Co's panoramic photo of the event. Note the camera tower opposite the northwest corner of the ring.

Status: Partially Found

On 26th December 1908, Tommy Burns defended his World Heavyweight Championship against Jack Johnson. Occurring in front of more than 20,000 at the Sydney Stadium, Johnson won the bout via decision following a police stoppage in the fourteenth round, thus becoming boxing's first black World Heavyweight Champion. The build-up towards the match and the fight itself was filmed by Spencer's Pictures, being released to cinemas internationally as The Burns-Johnson Fight.

Background

Tommy Burns had captured the World Heavyweight Championship by defeating Marvin Hart by decision on 23rd February 1906.[1][2][3][4] At only 5'7" and weighing around 170-180 lbs, the Little Giant of Hanover was the smallest boxer to have ever claimed the belt, having defeated significantly more imposing challengers via his agility and surprising reach.[5][4][2][3] By December 1908, Burns was champion for nearly three years and achieved history by earning KO victories over Bill Squires, Gunner Moir, Jack Palmer, Jem Roche, Jewey Smith, Bill Squires twice more, and Bill Lang in consecutive fights.[1][2][4] Only Larry Holmes has tied Burns' record of eight consecutive successful world title defences by KO.[5] These wins allowed him to enjoy a financially lucrative career, with him successfully defending the belt 12 times.[2][3][4][1] He is also credited for starting the process of the belt actually being defended across the world.[4][5]

While Burns' talent cannot be understated, the circumstances surrounding his title shot against Hart reflected a racially divided American society.[2][4][3] The consensus within the boxing world indicated that Jack Johnson among others were seemingly more worthy contenders.[2][4] Standing at 6'1⁄2" and weighing between 200-205 lbs, the formidable Galveston Giant from Galveston, Texas had garnered a reputation for being one of the top boxers of the mid-1900s.[6][7][8] However, Johnson et al had a barrier unrelated to their talent; they were black, and American boxing society was adamant about preventing boxers of different ethnicities from competing against each other.[9][8][2][4] Black boxers, unsurprisingly, were often overlooked when promoters searched for the next world title contender due to this "color bar".[2][6][4] For instance, a factor in promoter Tom McCarey's decision to pick Burns over Johnson was simply because he was of white ethnicity.[2][9][4] Previously, Johnson had challenged champion James J. Jeffries, but the latter elected to retire rather than risk threatening the color bar.[10][8][3]

Thus, Johnson initially accepted reigning as the World Colored Heavyweight Champion, defeating Denver Ed Martin via decision on 3rd February 1903.[11][8][7] As its name implies, the World Colored Heavyweight Championship was exclusive to black boxers and became the top prize for them during boxing's color bar era, dating back to 1876.[11][8] However, a greater opportunity arose for Johnson when Burns became World Heavyweight Champion.[3][4][8] Unlike most other top white boxers of the era, Burns openly insisted he would fight any prominent opponent, regardless of their ethnicity or nationality.[4][3][8] Even before becoming the World Heavyweight Champion, Burns faced criticism in the United States for willingly fighting black opponents, as well as for being a patriotic Canadian rather than accepting US status.[3][4] Upon defeating Hart, the new champion exclaimed that he would need to fight all challengers to truly justify his world champion status.[4][3][8] Similarly, he also elected to face opponents outside North America, including in London, Paris, and Sydney.[2][1][3][4] Among the hopefuls included Jewey Smith, the first Jewish boxer to challenge for the belt.[4][1]

Johnson used Burns' statement to his advantage, having travelled across the world and issued numerous challenges that followed Burns' successful title defences.[12][13][3][4] He also built up his win record, defeating fellow challengers like Lang, as well as KOing former champion Bob Fitzsimmons on 17th July 1907 in just two rounds.[14][7][12] He also remained unbeaten during defences of his World Coloured Heavyweight Championship.[7][11] Initially, Burns refused to face Johnson.[15][3][2] However, this was not because the Canadian had gone against his word.[3][15] Rather, as Johnson also noted in interviews, he realised a clash with the Galveston Giant would draw immensely, and he sought a major pay-out accordingly.[3][12][15][13] While Johnson criticised Burns' financial motive for delaying the bout, he still praised the champion for breaking the color bar guideline in the 13th May 1908 issue of The Tatler.[3][12]

Ultimately, both boxers soon got their wishes granted as Australian promoter Hugh McIntosh also predicted the match's lucrative nature.[16][9][13] When the US Navy's Great White Fleet visited Sydney on 20th August 1908 and triggered widespread celebrations, McIntosh ordered the construction of Sydney Stadium and paid Burns $20,000 to defend the belt twice in Australia.[17][9][13][16] Burns beat Squires at Sydney Stadium on 24th August, before he outmatched Lang a week later at the South Melbourne Stadium.[1][9][13][16] Now with a $50,000 surplus, McIntosh was able to cater to Burns' asking price for a match with Johnson: $30,000, worth about $1 million in today's money.[12][13][4][3][15] It was the highest pay-out for any boxing match up to that point.[18][4][14] This would be guaranteed regardless on whether Burns won or lost, with the Canadian pragmatic about his chances despite American and Australian outrage for him accepting the challenge.[4][12][3][15] Meanwhile, Johnson received a guaranteed $5,000.[13][14][3][2] While he was aghast by the low pay-out, common for black boxers back then, he reluctantly accepted it as the bout was his only realistic opportunity to win boxing's coveted prize.[13][3] Plans for Jefferies to referee the match were scrapped when he demanded $5,000.[15] Instead, McIntosh himself became the official.[4][15]

The Fight

The bout took place at Sydney Stadium on Boxing Day, with over 20,000 in the stands and a further 30,000 stationed outside the ground.[19][20][9][4] Unsurprisingly, the match was a huge success for McIntosh, generating £26,200 in profit.[9][4] The bout reportedly occurred during cloudy conditions, narrowly avoiding light rain that transpired earlier that morning.[21] Heading into the fight, it was reported by The New York Times that Burns was the 5-4 betting favourite, in a match declared of utmost importance for any predominantly English-speaking nation.[14] On the day of the bout, it was increased to 7-4.[19] However, concern arose within the Burns camp, as a weigh-in revealed his weight had decreased from an average 180 to just 168 lbs.[4][19] He was now 23 lbs lighter than his opponent, with speculation Burns' conditioning was affected by influenza.[4][12] The defending champion insisted on the bout, however, due to the big guaranteed money involved.[4]

Before Round 1 commenced, the mind games had already begun.[19][3][4][12] Johnson placed bandages on his hands, which forced a Burns' inspection to determine whether they were concealing something.[19] Burns himself taped his elbows, resulting in an infuriated Johnson demanding he remove them before the fight began.[19] Burns insisted on them, and McIntosh claimed the bandages did not violate any rules. However, Johnson's demands won over as Burns removed them to avoid the bout being declared a no-contest.[19] It was also alleged Burns used racist language during the contest.[3][12] While one could suggest he was reflecting the racist values of many white North Americans of the era, others speculate he was simply harnessing such taunts to gain a psychological advantage crucial for fighting bigger opponents.[3] Burns certainly had crowd support on his side, as Johnson received some scorn from the Australian press for his extravagant lifestyle.[9]

The bout began at 11:15 a.m. AEST.[19] Ultimately, Burns and his supporters' confidence approaching the clash proved completely unfounded, as Johnson took the initiative from Round 1 onwards.[19][20][4][12] After some sparring and body blows commenced, Johnson secured an early knockdown via an uppercut.[19][20][4][12] Burns later alleged McIntosh had directed him into a vulnerable position which resulted in the uppercut landing.[4] It took eight seconds for the champion to recover, and he suffered an immediate right hook to his head upon getting up.[19][20] Despite Johnson suffering a right hook to his chin, the challenger retaliated with a left hook and a kidney blow.[20][19] The second round saw Johnson yell "Come right on!".[19] Burns charged forward, only to be knocked down via a right hook to the chin.[19] He instantly rebounded but faced numerous subsequent head blows which resulted in his left eye swelling and his mouth bleeding.[19][20] Stomach blows also affected the defender's stamina.[19] Round 3 provided Burns a morale booster when he landed some right hooks and rib blows.[19] In retaliation, Johnson targeted his foe's kidneys and left eye.[19][20] His confidence only grew from there, asking his handlers post-round "What do you think of him?".[20]

Round 4 witnessed some taunts being directed at one another.[19] If Burns was indeed spouting racist remarks, it did little to impact Johnson's performance, as the latter landed a right rib blow, followed by a left body shot.[19][20] Burns' right hook was countered with a powerful right to the jaw, with Johnson adding a left hook to the head shortly afterwards.[20][19] Despite the punishment inflicted in the first four rounds, Burns was seemingly revitalised in the fifth and attempted to find a possible knockdown opportunity.[19][20] He landed a right hook and several body blows, before goading Johnson once more.[20][19] The challenger retaliated with a left stomach blow followed by a right hook to the jaw.[19][20] He landed another before the round ended.[20] Round 6 indicated just how on top Johnson was.[20][19] After landing a dozen rights onto his foe's ribs, Johnson tanked retaliating body blows, laughing and taunting his opponent with questions like "Who taught you to hit? Your mother?" in the process.[4][19] He also managed to trap Burns in a corner, landing more right body blows.[19][20]

By the seventh round, it became clear Burns' strength was deteriorating.[20][19] He was unable to defend himself against a rapid fire of right hooks, which inflicted easily visible damage to the right side of his face.[20][19] Though Burns landed a left to the jaw, his right eye was subject to a major beating, causing it and the right side of his face to become puffed and discoloured.[20][19] Some rib shots were enough for another knockdown, though the champion recovered after a few seconds.[19][20] Burns suffered more head trauma in Round 8, with his blows dealing little in return.[19] It led to calls for a stoppage, but Burns insisted on continuing.[4] Round 9 was more a battle of taunts than fighting, though the fact Johnson looked almost untouched compared to Burns again showcased the challenger's ongoing dominance of the bout.[19][20] Even though he was also becoming fatigued by Round 10, Johnson's blows remained powerful in comparison to the defender's.[19][20]

Round 11 began with Johnson landing a powerful right hook, though Burns did avoid some follow-up blows.[20][19] During clinches, Burns suffered numerous kidney blows and succeeded only in humouring the challenger.[20][19] The Canadian remained valiant, adopting an aggressive streak by the round's end.[20] Alas, he could only limp back to his corner.[19][20] Round 12 ended with Burns' injuries worsening; the left side of his face became swollen, as was his jaw after it received another six hooks.[19][20] The subsequent round led to a growing concern for the defender's condition; a dominant performance from Johnson resulted in Burns' mouth severely bleeding and doubling in size thanks to swelling.[19][20] Johnson also targeted the right eye.[19] Post-round, the police, led by Superintendent James Mitchell, were debating on when to prematurely end the encounter, with a consensus achieved for doing so in Round 14.[19]

McIntosh spoke to Burns beforehand, who valiantly insisted he could compete.[19][4] Thus, the promoter requested no police interference as the match went into the fourteenth round.[19] Burns countered a left with a right rib blow, but a Johnson right hook to the jaw secured another knockdown.[19][20] The champion managed to get up on the count of eight.[20][19] Capitalising on Burns' fatigued nature, Johnson smashed a left into his foe's forehead.[20][19] That was enough for Mitchell to demand the bout be stopped immediately despite Burns' protests.[20][19][4] McIntosh subsequently declared Johnson the winner via decision.[19][20][4][7] While he was not the first black world champion in general, as George Dixon, Joe Walcott, and Joe Gans all previously won world championships in lower weight categories, Johnson broke the final barrier by becoming the first black World Heavyweight Champion.[22][12]

The result devastated the predominantly white audience, who were silent following the decision.[9] After around twelve minutes, most had departed the stadium.[9] Post-fight, Burns accepted defeat, stating "I did the best I could and fought hard. Johnson was too big and his reach was too great".[19] A few days later, he expressed apologies for losing the championship and hoped for a rematch in the future.[23] At around 9:45 p.m. EDT, New York among other American cities learnt of the result.[19] It triggered both celebrations among the black media and scorn primarily around conservative regions.[19][9][15][12] Vocal critics included Jeffries, who believed Burns had sold both his and white people's pride in letting a black man challenge and subsequently win boxing's top prize.[4][15][12] He, among other top boxing stars like Fitzsimmons, did predict that Johnson would win going in, however.[19] Author Jack London declared that the so-called "fight" was non-existent due to Johnson's utter dominance of it, and called upon Jeffries to "rescue" the white man.[15][9][12] Meanwhile, McIntosh praised both boxers for fighting relatively cleanly, though he believed Johnson could have ended the fight much earlier had he desired to.[24]

The Film

The lucrative nature of boxing films since The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight in 1897 meant that it came as no surprise McIntosh commissioned the recording of the upcoming Burns-Johnson bout.[25][26][27][21] The promoter brokered a deal with the boxers, which saw Burns receive $1,750 for filming rights plus two London tickets totalling $1,200.[14] This meant that his net pay for the bout topped $33,000.[14] He would also receive film royalties.[8] In comparison, Johnson earned an extra $500.[14]

Some sources claim prominent Australian film producer Raymond Longford helped film the fight, but he was involved with a May Renno Dramatic Company production during that time period.[21][26] Pathé Frères were also reportedly involved, though in actuality, Cosens Spencer as part of his company Spencer's Pictures was commissioned to lead filming.[28][29][21] McIntosh later, however, mentioned that at least two other fight films were being produced, one from a "leading French firm".[24] Ultimately, the promoter selected Spencer's recording for worldwide circulation, deeming it of superior quality thanks to Spencer's Picture's greater knowledge of Australia's climate.[24] The work would be titled The Burns-Johnson Fight, with some newspapers also promoting it as Burns-Johnson Contest.[21] It is possible therefore that Pathé Frères were involved in some capacity, but their work was ultimately an "unnecessary expense" according to McIntosh, being scrapped in favour of Spencer's production.[24][29] The work's production budget was reported at £5,000.[30] Some of this originated from £2,000 worth of cameras and film.[27] Helping the production was the cloudy weather, noted as being "ideal" for recording according to the 30th December 1908 issue of Sydney Sportsman.[23]

Unlike previous boxing films, which focused exclusively on the fight itself, The Burns-Johnson Fight aimed to additionally document the fight's build-up and aftermath.[31][21][24][26] To that end, the film reportedly detailed the personal lives and training regimes of each boxer.[21][24][31] Beginning with McIntosh providing each boxer with their respective cheques, it then showcased Burns' training at Medlow Bath, while Johnson built himself up at Botany.[32][31][21] Aside from sparring with fellow boxers, it also revealed the two engaging in swimming, motoring, hunting and climbing, likely to illustrate the strong commitment both held in the preparation for the bout.[33][34][21][24][31] On Boxing Day, footage of the boxers' spouses and the crowd entering Sydney Stadium was shown, followed by the fighters' entrances.[33][21][24] All 14 rounds would be shown in their entirety before the film ended with the despondent audience leaving the vicinity.[21][24]

Ernest Henry Higgins was hired as the main cinematographer.[21][26] To record the fight within an ideal location, a 5-metre or 16-foot camera tower was erected within close proximity of the ring's northwest corner.[21][26][27] Tony Martin-Jones' analysis of a Kerry & Co. panoramic photo containing the camera tower indicates it may have contained up to four cameras within its vicinity.[21] At the very least, two cameras captured the film's surviving scenes.[21][26] One can discern this from the differences in light quality from each camera.[21] The fight was successfully recorded, though the first copy was hastily processed so that it could be showcased at the Sydney Stadium on 28th December.[31][21] Thus, as McIntosh himself admitted, the initial showcased recording suffered in terms of quality, losing some rounds and other footage as a consequence.[31][21] Nevertheless, The Burns-Johnson Fight would be properly processed two days later.[31][21]

The Burns-Johnson Fight proved a commercial and critical success.[21][24][31] At least 7,000 attended the inaugural Sydney Stadium; by the time it was taken out of circulation in Australia, the film had grossed £3,852 in Sydney and Melbourne alone.[31][21][24] Melbourne in particular saw a surge in interest, quickly selling out cinemas and forcing hundreds of late cinemagoers to wait for later showings.[35] The film quickly made its way across Australia, with distribution in South and Western Australia, as well as Tasmania and Victoria, being conducted by Allan Hamilton.[36][37][32][34] To ensure some exclusivity, only one film copy would sometimes travel interstate.[32] Showings in America and Europe were also common throughout 1909, with Gaumont-British having struck a £7,000 deal with McIntosh for United Kingdom distribution rights.[21] Spencer himself had agreed to film the occasion in exchange for 50% of screening rights.[38] This proved a lucrative deal, for the 17th September 1930 issue of Everyones reported he made £15,000 from the work.[38]

A private showcase of the boxers' regimes occurred at the Queen's Hall in Sydney for the Australian media.[39] The 12th December 1908 issue of The Newsletter praised the work's quality and deemed the inclusion of training footage as a "very fine idea".[39] Meanwhile, Sydney Sportsman declared the film as featuring a "most perfect series of pictures of a world-stirring event", primarily thanks to the ideal weather for the occasion.[23] Finally, the 6th January 1909 issue of Referee noted a screening at the Melbourne Town Hall also provided artificial sound, including for the audience's reaction upon the police stoppage, which it noted was realistic enough to deceive most spectators.[37] It also observed the crowd, predominantly male but containing a decent share of women, was well invested in the action, even laughing during lighter-hearted events and becoming equally vocal as the artificial crowd sounds upon the match's end.[37]

Aftermath

Burns continued fighting in 1910 following a two-year hiatus, though he never challenged for the World Heavyweight Championship again.[4][1][2] He captured the Australian Heavyweight and Commonwealth Boxing Council Heavyweight belts from Lang on 11th April 1910, as well as the vacant Canadian Heavyweight Championship from Bill Rickard on 8th August 1912.[1][4][2] He fought four more bouts, his last being a loss to Joe Beckett on 16th July 1920 with the Commonwealth Boxing Council Heavyweight Championship on the line.[4][1] The Beckett bout proved he was well past his prime, contributing to his retirement from the ring.[4]

Alas, despite accumulating significant revenue from his world title bouts, Burns' businesses failed and he lost the majority of his savings during the Great Depression.[4] His reputation as a strong world champion was tarnished following the Johnson fight, particularly by Jeffries and London who claimed Johnson won not by ability but because his opponent was weak.[4][3][2] After becoming an evangelist, Burns passed away from a heart attack on 10th May 1955, aged 73.[40][4][15][2] His passing was almost completely ignored, as just four people attended his funeral, being buried in an unmarked grave.[4] However, Burns' legacy has since been cemented, being declared among Canada's greatest athletes and one of the top world champions of his era.[4][3] More so, Johnson among others credited Burns for temporarily breaking the color bar in boxing.[4][3][5] In 1909, Johnson stated "let me say of Mr. Burns, a Canadian and one of yourselves, that he has done what no one else ever did, he gave a black man a chance for the championship. He was beaten, but he was game."[4][3]

As for Johnson, a successful though controversial reign as champion emerged.[41][42][6] Amazingly, he initially insisted on the color bar for his defences, deeming facing white boxers as more lucrative bouts against black counterparts.[42] Among the early challengers included Jeffries, who was coaxed out of retirement to become the "Great White Hope" versus a man who was declared by some media outlets as the most hated within the United States.[43][10][41][6] The match took place on 4th July 1910 in Reno, Nevada, under the promotion of Tex Rickard.[13][43] Attempts by McIntosh to host the event failed, as Johnson remained resentful over his low pay-out from the Burns fight.[13][24] The supposed "Fight of the Century" proved anything but, as a past-his-prime Jeffries was defeated by the champion in 15 rounds.[43][7][41][6] Following this, over 20 fatalities were reported in the ensuing country-wide race riots.[41][43][6]

Though Johnson remained a strong champion for years, his life outside the ring cost him significantly.[41][6] Growing criticism emerged surrounding his extravagant lifestyle from both white and African American communities, with him also marrying several white women when interracial marriages were generally considered taboo in American society.[41][6] In 1910, the Mann Act was introduced, which made it a felony for one to transit females on an interstate basis for illegal actions, most prominently prostitution.[44][43] Johnson, while still champion, was arrested twice under this act, for allegedly transporting future wife Lucille Cameron and Belle Schreiber for prostitution activities.[45][41] While he was acquitted of the former charge, an all-white jury convicted him of the latter, and he was sentenced to a year and one month in prison on 4th June 1913.[45][41]

He ultimately escaped to France while out on appeal, and over the next few years, defended the belt a few times in Europe.[45][41][7] This included a draw against Battling Jim Johnson on 19th December 1913, the first time the World Heavyweight Championship was contested by two black boxers.[46][47][7] As Europe was plunged into the First World War, Johnson defended his title in South America.[45][41][7] On 5th April 1915, after receiving a guaranteed $30,000, defended the belt against Jess Willard in Havana.[48][18][45][7] He ultimately lost by KO, with Willard re-imposing the color bar once more.[48][45][41][7] No black boxer would challenge for the World Heavyweight Championship again until 1930.[45] In 1920, Johnson returned to the United States to serve the rest of his sentence.[45][41] After being released on 19th July 1921, Johnson continued boxing until 27th April 1931, where he defeated Brad Simmons by KO in his final bout.[45][7] On 10th June 1946, he passed away in a car accident aged 68.[49][43][41] 105 years following his conviction under the Mann Act, Johnson was posthumously pardoned by President Donald Trump on 24th May 2018.[50][41]

Availability

According to McIntosh in the 16th January 1909 issue of Eastern Districts Chronicle, The Burns-Johnson Fight lasted around two hours.[24] Ultimately, the full version of the production has been lost to time.[26][21] While it is unclear regarding the reasons for its disappearance, worldwide versions were extensively edited.[21] For instance, the Gaumont-British version repeated some highlights, cut out other footage deemed as redundant, and included Gaumont intertitles.[21] According to Tony Martin-Jones, surviving footage totalling 13:23 in length preserved at the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia likely originated from the British cut.[51][21]

Of the available footage, most of it stems from the first, fifth, eighth, eleventh, and final rounds, with footage from the others being considered completely lost.[21] Round 14 is incomplete, as it lacks the fight's conclusion.[21][26] This led to speculation that the Sydney police had actually demanded filming cease prior to the bout's stoppage.[26][21] However, Referee indicated the fight's end was included in the final version.[37][21] Obviously, said footage has also become lost media, though the reason behind its disappearance remains unclear.[21] The surviving footage has aired on numerous television documentaries and has also been subject to restoration and colourisation projects.

Gallery

Videos

See Also

- Barbara Buttrick vs Gloria Adams (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1959)

- Bill Lewis vs Freddie Baxter and Archie Sexton vs Laurie Raiteri (lost television coverage of boxing matches; 1933)

- Cassius Clay vs Tunney Hunsaker (partially found footage of boxing match; 1960)

- Corbett and Courtney Before the Kinetograph (partially found early boxing film; 1894)

- England vs Ireland (lost television coverage of boxing matches; 1937)

- Evander Holyfield Championship Boxing (lost build of cancelled Game.com boxing game; 1999)

- Exhibition Boxing Bouts (lost early television coverage of boxing matches; 1931-1932)

- The Fighting Marine (lost Gene Tunney drama film serial; 1926)

- Gene Tunney vs Jack Dempsey (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1926)

- Gene Tunney vs Jack Dempsey (partially lost radio coverage of "The Long Count Fight"; 1927)

- Georges Carpentier vs Ted "Kid" Lewis (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1922)

- Heavyweight Champ (lost SEGA arcade boxing game; 1976)

- Jack Dempsey vs Billy Miske (lost radio report of boxing match; 1920)

- Jack Dempsey vs Georges Carpentier (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1921)

- Jeffries-Sharkey Contest (partially found footage of boxing match; 1899)

- Jo-Ann Hagen vs Barbara Buttrick (lost radio and television coverage of boxing match; 1954)

- Johnny Ray vs Johnny Dundee (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1921)

- Len Harvey vs Jock McAvoy (partially found footage of boxing match; 1938)

- Leonard-Cushing Fight (partially found early boxing film; 1894)

- Marcel Cerdan vs Lavern Roach (lost footage of boxing match; 1948)

- Rocky (lost deleted scenes of boxing drama film; 1976)

- Super Punch-Out!! (lost beta builds of SNES boxing puzzle game; 1994)

- Title Defense (lost build of cancelled boxing simulation game; 2000-2001)

- Uncle Slam and Uncle Slam Vice Squad (lost iOS presidential boxing games; 2011)

External Links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 BoxRec summarising Burns' matches. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 International Boxing Hall of Fame page on Burns. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 The Cardboard Junkie providing a detailed biography on Burns and his legacy. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 4.29 4.30 4.31 4.32 4.33 4.34 4.35 4.36 4.37 4.38 4.39 4.40 4.41 4.42 4.43 4.44 4.45 4.46 Ringside Report documenting the life and career of Burns and defending his record and legacy. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Library and Archives Canada summarising Burns' accomplishments. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 International Boxing Hall of Fame page on Johnson. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 BoxRec summarising Johnson's matches. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 PBS documenting Johnson's rise through the ranks, hindered by his ethnicity. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 Woollahra Municipal Council documenting the fight, its promotion, and the film of it. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Open Culture documenting Jeffries refusing to defend the World Heavyweight Championship against Johnson, before later challenging him in 1910. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Archive Eastside Boxing summarising the history of the World Colored Heavyweight Championship. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 The Fight City summarising Johnson's insistence on a title fight and Burns' confidence heading into it. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 13.9 Tex Rickard documenting how McIntosh promoted the bout and Rickard's promotion of "The Fight of the Century". Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 25th December 1908 issue of The New York Times previewing the bout. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 Boxing News Online summarising the contest and aborted plans for Jeffries to referee it. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 International Boxing Hall of Fame page on McIntosh. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ Royal Australian Navy detailing the visit of the Great White Fleet on 20th August 1908. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Jess Willard noting the $30,000 pay-out was the highest in boxing history by 1908, and how it influenced Johnson's demands for a fight against Willard. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 19.13 19.14 19.15 19.16 19.17 19.18 19.19 19.20 19.21 19.22 19.23 19.24 19.25 19.26 19.27 19.28 19.29 19.30 19.31 19.32 19.33 19.34 19.35 19.36 19.37 19.38 19.39 19.40 19.41 19.42 19.43 19.44 19.45 19.46 19.47 19.48 19.49 19.50 19.51 26th December 1908 issue of The New York Times providing an extensive report on the bout. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 20.00 20.01 20.02 20.03 20.04 20.05 20.06 20.07 20.08 20.09 20.10 20.11 20.12 20.13 20.14 20.15 20.16 20.17 20.18 20.19 20.20 20.21 20.22 20.23 20.24 20.25 20.26 20.27 20.28 20.29 20.30 20.31 20.32 30th December 1908 issue of Border Watch reporting on the fight. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 21.10 21.11 21.12 21.13 21.14 21.15 21.16 21.17 21.18 21.19 21.20 21.21 21.22 21.23 21.24 21.25 21.26 21.27 21.28 21.29 21.30 Tony Martin-Jones' film history notes providing extensive detail on the filming of the bout, also debunking several rumours. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ BOXRAW summarising black boxing milestones. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 30th December 1908 issue of Sydney Sportsman reporting on the film's opening night and noting the "most perfect series of pictures". Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 24.00 24.01 24.02 24.03 24.04 24.05 24.06 24.07 24.08 24.09 24.10 24.11 24.12 16th January 1909 issue of Eastern Districts Chronicle reporting on McIntosh's comments surrounding the fight and its filming. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ Silent-ology detailing The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight's successful box office reception. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 26.6 26.7 26.8 National Film and Sound Archive of Australia summarising the film and surviving footage of it. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 19th December 1908 issue of The Brisbane Courier reporting on the preparations surrounding filming. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 29th December 1908 issue of The Telegraph reporting the film was produced by Pathé Frères. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 14th February 1909 issue of Sunday Times reporting Pathé Frères did not produce the film. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 1st January 1909 issue of Illawarra Mercury promoting the film and noting its production budget was £5,000. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31.6 31.7 31.8 29th December 1908 issue of Evening News reporting on the film's unveiling on 28th December and summarising the scenes involved. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 28th December 1908 issue of The Register reporting on the film's completion and how only "one film" would travel between two states Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 10th February 1909 issue of The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate promoting the film for a Parramatta Town Hall screening and noting some of its scenes. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 4th March 1909 issue of Southern Times reporting on the film's upcoming showcase in Lyric Theatre and summarising the film's scenes. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 6th January 1909 issue of The Register reporting on the film's big reception in Melbourne, forcing many to be turned away at cinemas. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 30th January 1909 issue of The Daily News reporting on Hamilton acquiring exclusive distribution rights across four states of Australia. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 6th January 1909 issue of Referee reporting on Hamilton's ongoing distribution of the film and providing a review of it. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 17th September 1930 issue of Everyones noting Spencer made £15,000 from the production. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 12th May 1955 issue of The Canberra Times reporting on the death of Burns. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 41.00 41.01 41.02 41.03 41.04 41.05 41.06 41.07 41.08 41.09 41.10 41.11 41.12 41.13 Britannica summarising Johnson's later career and legacy. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Archived Hudson Reporter summarising the controversy over Johnson retaining the color bar for several years. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 43.5 The Los Angeles Times documenting the "Fight of the Century". Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ PBS detailing the Mann Act. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 45.5 45.6 45.7 45.8 PBS detailing Johnson's arrest and conviction under the Mann Act, and his later World Heavyweight Championship defences. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ On This Day noting Johnson's match with Battling Johnson was the first World Heavyweight Championship match between two black boxers. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 20th December 1913 issue of The New York Times reporting on the Jack Johnson-Battling Johnson match. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 The Fight City detailing Johnson's lost to Willard. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ 11th June 1946 issue of The New York Times reporting on Johnson's death. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ The New York Times reporting on Johnson receiving a posthumous pardon by President Donald Trump. Retrieved 24th Sep '23

- ↑ National Film and Sound Archive of Australia stating it holds a 13:23 cut of the film. Retrieved 24th Sep '23