The Boat Race 1927 (lost radio coverage of rowing race; 1927)

The Boat Race 1927 was the 79th edition of Oxford and Cambridge University's prestigious side-by-side rowing event. It occurred at the River Thames' Championship Course on 2nd April and saw Cambridge come from behind to beat Oxford by three lengths, marking its fourth consecutive Boat Race victory. The event is also historic from a media standpoint, as it was the first Boat Race to receive live radio coverage.

Background

Having been held on a mostly regular basis since 1829,[1] the Boat Race swiftly became among the most anticipated annual sporting events in the United Kingdom, alongside the FA Cup Final and the Grand National.[2][3] Out of all contests, the Boat Race is certainly the most contentious between the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge as whoever won earned bragging rights that out-trumps all other results.[4] The event has been held on neutral waters, namely the Championship Course at the River Thames lasting 4.2 miles or 6.8 km.[5][3] By 1927, the competition's prestige had solidified.[2] As Issue 182 of Radio Times noted, the Boat Race became an annual trip for Londoners, who remained passionate about the event despite most sharing no connections with either university.[2] Heading into the 1927 edition, Cambridge was on a three-race winning streak, but Oxford led in the overall standings 40-37.[1]

The earliest known Boat Race-related broadcast occurred on 23rd March 1923 as part of Children's Stories.[6][7] It simply provided an explanation of the event to a children's audience.[6] Aside from other relevant talks, very few Boat Race broadcasts emerged prior to 1927.[7] In 1925, the British Broadcasting Company's director-general John Reith was keen to provide radio coverage on several major sporting events, including the Boat Race.[8] However, Britain's radio advancements greatly worried the press media, whose sales partially depended on providing sports results.[9][10] Thus, the print media lobbied the government to prevent radio from covering live sports or even providing post-match results, thwarting early attempts at covering the Boat Race.[8][10][9] But on 1st January 1927, the British Broadcasting Company became a Royal Charter and transformed into the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC).[11][10] Suddenly, the BBC was now legally able to cover live sports, beginning with the England-Wales rugby union match on 15th January.[12][10]

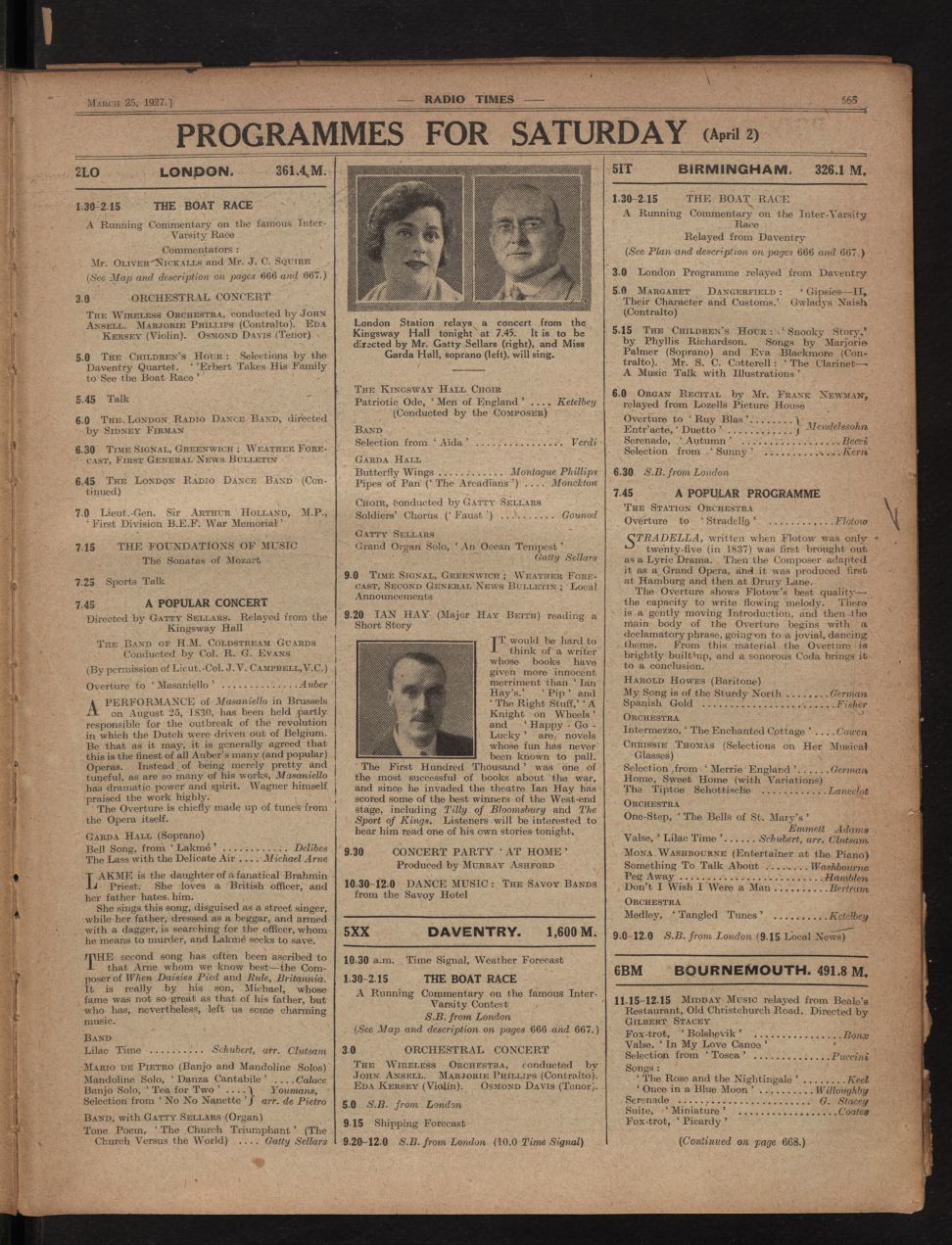

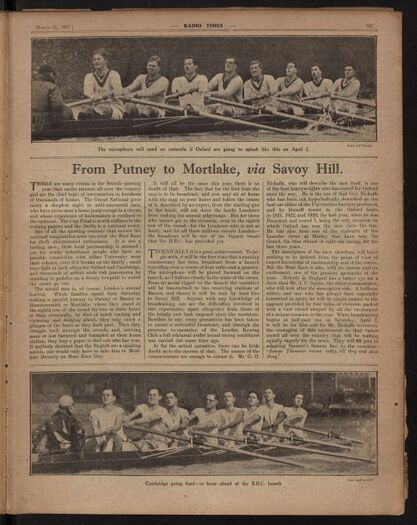

The BBC's subsequent coverage of the 1927 Calcutta Cup on 19th March was also pivotal in the inaugural Boat Race broadcast, as it became the first British sporting event to receive fully live outdoor commentary.[13][14] The subsequent Boat Race broadcast was naturally deemed a bigger technological challenge, as a running commentary would require one to follow the boats across the 4.2 miles of the Thames.[15][16][2][13] Producer Lance Sieveking and race umpire Charles Burnell agreed to allow the latter's launch boat, the Magician, to be equipped with the necessary radio transmission equipment including an aerial.[15][2] During the race, two receiving stations located at Barnes would tune in and receive coverage via the Magician's aerial.[16][13][2] The stations would then redirect it to BBC Radio London's headquarters in Savoy Hill,[17] whereupon the broadcast would be transmitted nationwide.[2] Joining Burnell in the Magician were the commentators Guy "Gully" Oliver Nickalls and John Collings Squire.[18][19][15][2] Nickalls had competed in the Boat Race for Oxford from 1921-1923, winning the 1923 edition as its president.[20][2] He would provide technical commentary for the race.[2] Meanwhile, poet John Collings Squire, most known for his poem The Survival of the Fittest and as the London Mercury's founder,[21] was brought on to provide a descriptive account for listeners.[2]

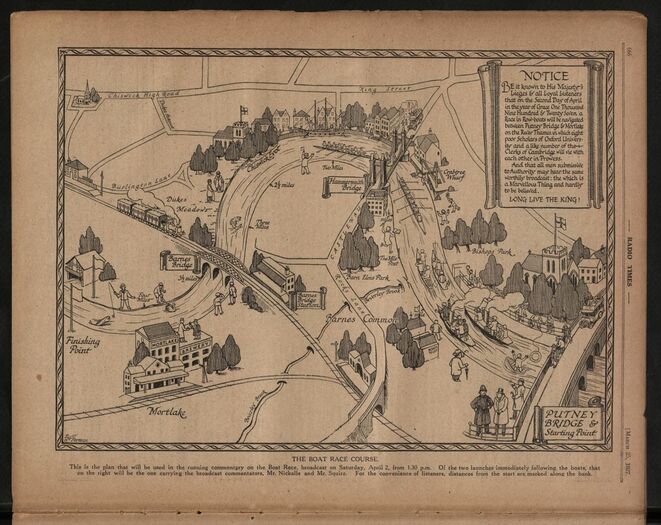

The coverage plan was highly complex for 1927.[2][15] Its success depended on the Magician, which not only carried the umpire and two commentators but also a pilot, four BBC engineers and equipment weighing more than 1,000 lbs.[15][16][13] As Issue 182 of Radio Times noted, no such broadcast had previously been achieved with a launch covering that distance.[2] Thus, the BBC and the London Rowing Club conducted an experimental broadcast of another Thames race held prior to 182's publishing on 25th March.[2] The results satisfied both parties, allowing the Boat Race broadcast to proceed.[2] Similar to its grid system used in football and rugby broadcasts, Radio Times published a plan of the Championship Course.[22][23] The plan listed the key landmarks and their distances from the start, allowing listeners to follow the race.[22] The BBC anticipated that listeners would be curious about how the Boat Race broadcast was even possible.[24] Hence, on 21st March, director of programmes Roger Eckersley conducted a talk concerning the challenges faced in broadcasting the Boat Race and the Grand National as well.[24] To educate and build excitement among the children, the Boat Race's history was narrated as part of Children's Hour on 28th March.[25] Sir Theodore Cook is also known to have conducted a Boat Race speech on 30th March.[26]

Nickalls recalled that he and Squire would place their foot on the other's whenever they had key information to passionately impart.[27][15] Neither had any idea if the broadcast had been achieved, only receiving confirmation post-race thanks to a congratulatory telegram from Reith.[15][27] Listeners generally praised the broadcast; a letter published in Issue 432 of Wireless World by an M. S. in Croydon expressed how they were enthralled by the broadcast, sharing the enthusiasm of Nickalls and Squire and being able to place themselves in the shoes of a spectator present at the Thames.[28] Wireless World agreed with this verdict, declaring it as the most popular outside broadcast for 1927.[28] Henceforth, the Boat Race became another major sporting event to receive annual live BBC coverage, with John Snagge fulfilling commentator duties from 1931 to 1980.[27] Eleven years later, the 1938 edition became the first to be televised live.[27]

The Race

In preparation for this race, Cambridge (aka the Light Blues) and Oxford (Dark Blues) conducted intensive training.[29] Oxford did their sessions in Shrewsbury and were considered the underdogs for the race, Cambridge having been deemed "well together and pleasing the critics" according to a British Pathé newsreel.[29] However, 1902 and 1903 Oxford rower George Drinkwater was unimpressed with the Cambridge selection and felt Oxford's coaching required improvement.[16] Richard Burnell noted that in general, neither side was seen as a top crew.[30] Oxford's president that year was James Douglas Wishart Thomson, who would later become a Scottish Unionist MP representing Aberdeen South.[31][32] Meanwhile, S. K. Tubbs became the Light Blue's president.[31] Weeks before the race, Oxford suffered a blow after their stroke rower W. S. Llewellyn contracted German measles, being replaced by A. M. Hankin.[33][16][31] The Boat Race's race summary believed the Dark Blues was showing signs they could achieve an upset until the loss of Llewellyn.[33] Their only crumb of comfort was that Cambridge's crew also lacked a strong stroke.[33]

A major concern sports organisers like the Football League held was whether live radio coverage affected overall attendance.[34] This clearly was not the case for the Boat Race as thousands stood themselves at the Thames' banks, eager to witness a good match-up.[35][33] As Oxford won the toss, they had the choice of starting station.[33] They opted to put the Light Blues in the Middlesex station, believing the Sussex start would give them an advantage in the high tide.[33][35][16] The race began at around 13:44 pm; initially, Oxford held the advantage.[33][35] While a canvas lead at Craven Steps was neutralised by Cambridge at Mile Post, the Dark Blues managed to gain a 3-second lead at Hammersmith Bridge and expanded it to a length at Chiswick Eyot.[33][35] However, Oxford's campaign was unglued after they approached significant headwinds.[33][16] Suddenly, Cambridge fought back thanks to a better stroke rate and had reduced two seconds of the Dark Blues' lead by Chiswick Steps.[33] Cambridge then took its own 3-second lead upon crossing Barnes Bridge.[33] With the final bend remaining, the Light Blues expanded its gap to three lengths or 10 seconds and thus confidently "come home alone" at Mortlake.[33][16][35][1]

With this victory, the Light Blues' fourth consecutive Boat Race win, it reduced the overall standings to 40-38.[1] This marked a turning point where Oxford suffered what Drinkwater described as "rot", being completely outmatched by Cambridge and criticised for producing second-rate teams throughout much of the 1930s.[30] Cambridge never lost a Boat Race from 1924 to 1936 and subsequently led 47-40 overall.[1] Significant restructuring was required before Oxford finally achieved glory again in the 1937 edition.[1][30]

Availability

The BBC's radio coverage of the 1927 Boat Race commenced when few live broadcasts in general were preserved.[36][37] The corporation did not begin regular recordings until the Blattnerphone was introduced in the 1930s, though even then preservation was mainly cost-prohibitive until the mid-1930s.[38][37] Within the BBC archives, it was ultimately confirmed that the oldest surviving radio sports recording is a 1932 re-enactment of the 1928 FA Cup Final.[39] Barring some miracle pirate recording of the broadcast, such as what transpired with the second Gene Tunney-Jack Dempsey boxing match,[40] it is more than certain the coverage is permanently inaccessible.[36] Likewise, the Children's Hour, Eckersley and Cook broadcasts were extremely unlikely to ever be preserved, thus making them forever lost as well.[7] Nevertheless, newsreels produced by British Pathé and Gaumont Graphic provide some footage of the race and the prior training sessions.[41][35][29] A photo of the Magician during the race also exists, while the broadcast itself was detailed in Issue 182 of Radio Times.[27][18][19]

Gallery

Videos

Images

See Also

- The Boat Race (partially found television coverage of rowing races; 1938-present)

- The Boat Race 1938 (partially found footage of rowing race; 1938)

- The Boat Race 1949 (partially found footage of rowing race; 1949)

- The Oxford and Cambridge University Boat Race (lost footage of rowing race; 1895)

External Links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 The Boat Race providing a list of Boat Race results. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Issue 182 of Radio Times previewing the race and its radio coverage. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The Telegraph summarising the history and prestige of the Boat Race. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ Cambridgeshire Live summarising the importance of the race for both universities. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ The Boat Race detailing the Championship Course. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The 23rd March 1923 Children's Stories broadcast as listed by BBC Genome. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 BBC Genome archive of Radio Times issues listing the earliest Boat Race-related radio broadcasts. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 International Radio Journalism detailing the BBC's failed early attempts at covering the Boat Race and other sports live. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Inclusive Masculinities in Contemporary Football detailing the concern press media had over radio broadcasting sports results. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Encyclopedia of Radio 3-Volume Set detailing how lobbying thwarted early attempts at covering live sports, which was rectified when the BBC became a Royal Charter. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ BBC on its history of being a Royal Charter. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ The Cultural Me summarising the BBC's coverage of the England-Wales rugby union match on 15th January. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 The Oxford & Cambridge Boat Race noting the 1927 Boat Race was the subject of the BBC's second live outdoors sports commentary. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ Issue 180 of Radio Times detailing the coverage of the 1927 Calcutta Cup. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 Archived The Guardian detailing the technological challenges faced in transmitting the race, and Nickalls' comments surrounding it. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 The University Boat Race – Official Centenary History detailing the race and its radio broadcast. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ BBC summarising its headquarters in Savoy Hill. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 BBC Genome archive of Radio Times issues detailing the coverage of the race. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Issue 182 of Radio Times listing the race coverage. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ Olympedia page on Guy Oliver Nickalls. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ Poetry Foundation page on J. C. Squire. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Issue 182 of Radio Times providing a plan of the Championship Course. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ On This Day summarising the grid systems Radio Times regularly published for early sports broadcasts. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Issue 180 of Radio Times detailing Roger Eckersley's Boat Race and Grand National broadcast speech. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ Issue 182 of Radio Times detailing the Children's Hour broadcast about the Boat Race. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ Issue 182 of Radio Times vaguely listing Sir Theodore Cook's Boat Race speech. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 BBC summarising the history and milestones of Boat Race media. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Issue 432 of Wireless World which contained a letter praising the broadcast, with Wireless World also listing it first among the most popular outside broadcasts of 1927 (p.g 83-84 and 854). Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 British Pathé newsreel reporting on the crews' training sessions. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 One Hundred and Fifty Years of the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race: An Official History noting the general reception of both teams heading in and the "rot" Oxford suffered following this defeat. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 One Hundred and Fifty Years of the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race listing the rowers of each team. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ The Times summarising the career of Sir Douglas Thomson. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 33.00 33.01 33.02 33.03 33.04 33.05 33.06 33.07 33.08 33.09 33.10 33.11 Archived The Boat Race report on the race. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ Spartacus Educational summarising the Football League's concern regarding radio coverage and stadium attendance, resulting in a live radio ban in June 1931. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 British Pathé newsreel of the race. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 BBC noting it did not start recording radio coverage until the early-1930s. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Library of Congress detailing how radio recordings only became relatively affordable in the mid-1930s. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ BBC noting it had no viable means of recording sound until the introduction of the Blattnerphone in 1930. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ BBC providing an extract of surviving radio coverage from the 1932 re-enactment of the 1928 FA Cup Final, the oldest sporting clip in its archives. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ Archived Boxing Noir on the pirate recording of the second Gene Tunney-Jack Dempsey boxing match. Retrieved 16th Jan '24

- ↑ Gaumont Graphic newsreel of the race. Retrieved 16th Jan '24